TimeZone.com Interview with Jeff Barnes, Co-founder of the Halter Barnes Watch

Interviewer: Richard Paige @ TimeZone.com

October, 2000

Click to see full-size image

Jeffrey Barnes was educated in Communication and Design.

Before forming Barnes Design Office, he developed communication programs at the corporate offices of Container Corporation of America, a division of Mobil Corporation.

He is experienced in advertising, brand and corporate identity, image development, corporate communications, direct mail, editorial design, still photography art direction and product design (furniture and timepieces).

His clients range from small business to multinational corporations in fields as varied as architectural products, business consulting, fashion, engineering, finance, furniture, technology, intellectual property, printing, office filing systems, publishing, real estate, retail, telecommunications, toys and transportation.

His work received approximately 150 local, national and international awards, and is included in the permanent collections of: Museum of Modern Art, New York; Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York; Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.; Staatliches Museum for Angewandte Kunst, Munich. It has also been published in America, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands and Switzerland.

He taught undergraduate and graduate levels of design at major universities and art schools, and lectured and judged exhibitions throughout the U.S.

|

RP: Richard Paige - TimeZone.com JB: Jeffrey Barnes |

RP: How did you ever get involved in producing a watch that defied modern manufacturing logic?

JB: If you don't do something different, you will be like everyone else. And if you're like everyone else, the buyer will choose a well-known brand over an unknown brand. This is why so many companies fail, lack of true innovation. So my idea was to find someone willing to create an outstanding design that would get attention and establish the name almost overnight. It was an experiment that I knew would work, especially because my specialty is corporate/brand identity and image development. I was right. But I did not plan to make just one outrageous watch for a few collectors. The design was part of an inspiration that could be applied to a much larger product grouping that shared the same look and character, but would be available to a wider audience.

RP: How did the watch collaboration evolve with Vianney Halter? Did you do the design concepts and he brought the watch to reality? Is it kind of like a singer and a songwriter: they each must depend on the other's expertise?

JB: It's a long story, but let me try to cover the main points. After about five years of watch research and design, I decided to make a trip to the Basel Fair. While I was impressed and had a great time in watch heaven, I walked away without any real contacts. It was after my return that I read an article in a watch magazine that a distributor of fine Swiss watches was located in Chicago, just a short distance from me. He was Joseph Penula, from Switzerland. I gave him a call and we met. Upon our first meeting I was told that the company he represented would not be interested in even seeing my designs. So that was that. Nothing happened for a while, but as we continued to meet, he noticed that I had a good grasp of the watch market in America. As our relationship became more relaxed, he confided in me that the distribution of fine watches in America was a difficult task if not fully supported by the company. It was then that he asked to see my designs. His response was very supportive, and he told me that he knew of a watchmaker in Sainte-Croix whose business was not doing well, and that the time might be right to approach him.

After the next Basel Fair, we drove to Sainte-Croix to meet Mr. Halter. Upon seeing my work he said my designs were not like so many who design things which cannot be made. I showed them in order, from the least exciting to the final and most revolutionary, what I later named the "Time Machine Perpetual Futura".

Click to see full-size image

Some time later he produced a rough prototype of the case which I was not happy with. I revised the design to what is now the "Time Machine Perpetual Antiqua". We agreed to start the project. In early December I went to Switzerland and stayed with Vianney for two weeks to begin the process of taking my rendered designs to basic engineering drawings. Mr. Penula followed a week after I arrived.

It was at that time that we began to understand just how badly Mr. Halter was doing. I even had to pay for his heating oil! Because of Mr. Penula's administration and manufacturing abilities, we were able to get things in order. Joseph also was highly inventive in bringing in work that helped Mr. Halter survive. That April a partially working prototype was presented at Basel.

Regarding the second question, about the singer/songwriter, it is a good analogy. Perhaps a better one is that of the composer/virtuoso. Up until the eighteenth century, it was common for great composers to perform their own compositions. The more famous names of Bach, Handle, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert are only a few. Shortly thereafter, it became more rare to be both composer and accomplished virtuoso. The same is true in watchmaking. Everyone is familiar with the great Abraham-Louis Breguet. His designs and technique are equally masterful. There were others too, such as Ferdinand Berthoud and Antide Janvier. It is also true that these great masters did not do all their own work. Breguet did not make his first tourbillon. Today, this is as true for watchmaking as it is for music. Either you are a designer or a watchmaker. By this I mean that with most master timepieces, the case, dial and crown show little innovation. In other words, you would not purchase the timepiece because of case innovation. Many people would argue that the movement is the only factor in buying a watch, but that is another topic. Usually a very traditional design is chosen which does not detract from their mechanics. And this is not the only area where a designer can have a big impact.

As to my relationship with Mr. Halter, I was the designer who initiated the innovation. I knew it was possible, and he agreed that it was unique and possible to build. I also designed the mystery rotor used in the watch. It is also important to recognize the necessity of staying alive while all this is taking place. Mr. Penula was very instrumental in this.

RP: I must admit when I first saw the "Time Machine Perpetual Futura", I was really taken back, I hadn't seen such an innovation of design with an in-house movement in many years. For the record, is the movement in-house? Also, what kind a manufacturing resistance did you have regarding the case: Was it too radical for most case manufacturers?

JB: The movement had to be unique since it had to follow the design, as the location of the various dials were quite unlike anything else. The movement started life as a double-barrel Lemania 8810. Perhaps 60% to 70% of the final movement required new parts. The complication was all new, a totally new caliber. It measured about 4.7 by 32 millimeters, and uses 43 jewels, and operates at 28,800 pulsations. It used the original plate, but two new custom bridges were made that can be seen through the open back. Now if you look at a photo you would say there is only one bridge. It was Mr. Halter's idea to confuse and eventually to impress his fellow watchmakers. And to a watchmaker this would indeed be difficult to comprehend. This was done by hiding the seam between the two bridges along the shadow of the Côtes de Genève decoration. The problem was that now there was nothing to look at for the non-watchmaker owner. Almost everything was covered! Exposing as much as possible would have enabled the best use of my mystery rotor, which enables the entire movement to be exposed. This is a good example of how Halter, the watchmaker, didn't understand the bigger issue of allowing the customer to get involved in the mysteries of the micro-mechanical wonder on his wrist. His need to impress his colleagues shows perhaps a professional insecurity. He insisted on doing this against our will and the result is anticlimactic for most of the watch-loving public.

As to your question regarding the case maker, Mr. Penula's persistence paid off by discovering a case maker who was persuaded to see potential in our vision. This was perhaps the greatest factor in realizing the case. Of course, the shear number of parts multiplied the complexity of the case over that of any other existing watch, but I believe there are other fine case makers who could have produced the case. So when you asked earlier if there was a relationship like a singer and songwriter, perhaps I should have included, that in order to survive, there had to be a publisher or agent as well. Joseph was as dedicated and tormented as anyone in realizing the zillions of details necessary to create a case, as well as manage Mr. Halter.

It's important to remember that, as a Latin proverb states, "Things hard to come by are much esteemed." We were not interested in doing something that was already done and easy to come by. The more a society or industry or profession is refined, the more difficult it is to do something special. There are at least three different shaped wooden toothpicks!

RP: What was the inspiration behind the Halter Barnes "Time Machine" watch?

JB: The futuristic thinking of Jules Verne. Doing something that could not be done, in the only way that it could be done. Let me explain. In the movie of the H. G. Wells classic, "The Time Machine," the seat in the machine was an old Victorian (?) chair. It was completely out of place in that futuristic contraption, but that's all they had. It didn't use a head rest or seat belts. There is a kind of "familiar strangeness" or unexpected juxtaposition that is very fantasy-creating. It is the past trying to predict the future.

Once the elements were understood, the application was consistent. For example: the rivets used in putting things together in Jules Verne's time, were used to hold the dials in place. They were also placed around the cylinder of the crown to enable it to be twisted. By the way, there are two rows of twelve white gold rivets and one large cabochon on the end of the crown cylinder, 26 pieces!

Of course the multiple dials had never been done before, at least that's what my research indicated. It was quirky, yet functioned well because the time and the date could be read protruding from under the cuff while most of the watch covered.

Click to see full-size image

RP: I was one of the original importers of the Halter Barnes watch to the USA, and to be honest with you, I was very disappointed and angry that the watches were unattainable both physically and economically, especially with such a pent up demand for the watches. What went wrong??

JB: You weren't the only one who was upset! Having gone through the entire process from conception through manufacturing and marketing, I can say we all learned how to DO it as well as how NOT to do it. As production began, Vianney gave us a completion date for a part, but when that date came, there was no product, only an excuse. What we learned was that he was good at developing a prototype watch, but was quite ignorant about the actual manufacturing process. Even his "mechanical drawings" were little more than working sketches. Because of this, time was required for trial and error testing. He would draw a computer sketch, make a prototype part, try it, see that it needed revision, revise the sketch, then make the revised part, then try it again, and on and on. Joseph had to deal with this problem with the customers. It was a no-win situation for him. If he gave a date and nothing happened, he was blamed. If he blamed Vianney, it looked bad for the company. As time progressed, Vianney became more and more difficult to deal with, he was too slow. Eventually the situation became unmanageable.

RP: I have seen your designs with the Vianney Halter name on them, was this planned?

JB: He is using them without my permission.

RP: What are you doing now? Are you working on anything new?

JB: I have been designing more timepieces and complication concepts. I'm finding that there are still very few products out there which offer truly differentiating design. I have just designed a new line of timepieces with the theme: an intriguing contradiction. It would appeal to a new generation of sophisticated enthusiasts. In addition, I have enough designs for six or seven lines! There is so much opportunity!

Click to see full-size image

RP: Do you have future plans for launching another watch line? what's the future look like for you in the watch business?

JB: Begin again with the knowledge and experience gained from this bittersweet experience. The Swiss watchmaking system can be very complicated, but now we know how to glide, well at least go through the process. We have made relationships with many fine individual craftsmen as well as great suppliers. Because of the difficulties of the past, proceeding is all the more important. Most people give up after a big difficulty. That's actually the time to keep going. It's the time when you've gained valuable experience that enables you to go the next step. I don't know of anyone who can do what we can do. The new millennium is a great time to start a new tradition!

RP: What is your next step?

JB: To keep on designing, innovating and planning. Unexpected things keep happening so you have to stay open and recognize opportunities. It's important for me to work with people who are fascinated with fine timepieces and with the culture that it represents.

RP: Culture? What do you mean by culture?

JB: So much of culture deals with contradiction. A ballerina expresses lightness or flying, yet has no wings. A renaissance painter gives insight into the soul of an individual who no longer lives. A chef combines ingredients you don't like into a creation that changes your tastes. All of these things developed through history by passionate people who cared about what they did, believing they could make a difference. Others followed who respected what had been done before them, and added their own innovation. This respect and appreciation is at the heart of culture. For me, culture is a layering of the best on top of the best.

With horology there is a similar effect. It gives us an insight into something transcendent, time, by using springs, gears, levers and dials. Few of us are able to conceive how to make a watch, or master fine cuisine, so it intrigues us. The mysterious is fascinating. And learning more about something can often increase appreciation, not diminish it.

Another contradiction is that the modern world rewards speed and impatience, but individualism develops through contemplation, which takes time. We are amazed by the speeds of technology, yet we're still moved by the beauty and refinement of a fine timepiece that required neither speed nor impatience. Xenophanes said "It takes a wise man to appreciate a wise man." The individual is still important in horology, both the maker and the user.

RP: What watches do you collect, and what brands do you find come closest to this concept of excellence in design?

JB: Since I can't purchase what I really want, I am more of an appreciator than a collector. Bertrand Russell said "To be without some of the things you want is an indispensable part of happiness." I should be very happy! If I were selecting a vintage automobile, my choices would be the Maserati 300s or a Ferrari 250 Short Wheelbase Berlinetta. I mention these because they are classics that still intrigue many years later. I was at a very impressionable age when I first saw them and heard them, and that is always a major taste-making factor. But beyond that, they are intuitive and very emotional, yet function in a totally appropriate and balanced way. A watch is much the same.

If I could choose a small selection of contemporary watches, I would have to say that the Patek Philippe perpetual calendar with split-second chronograph is magnificent, and has great presence without being ostentatious. I only wish it had a 12 hour register. Of course the mechanics are exquisite. For personal reasons I have always been drawn to the Audemars Piguet Starwheel, but I would order it with a white gold case and white gold guilloché dial to match the exposed mechanics. It would have to be special ordered. The Breguet Perpetual Calendar with asymmetric dials is also quite amazing. I remember when I first became aware of it. The dials and functions are so modern yet also full of character that can come only through many decades of development. In the case of some multi-dial Breguet watches, the only problem is the delicacy of the type. It is very thin, and only readable by the finest vision. Of course I have great appreciation for individual watchmakers like Philippe Dufour and François-Paul Journe, and for the recent reintroductions like A. Lange & Söhne. It's unfair to stop now, but I could go on and on.

Responding to a watch is a very personal thing. Being a typographer, I appreciate quality dials that are not gaudy or heavy handed. Good type and increment markings are very subtle elements that reveal the sensitivity of the maker, and help readability through contrast and hierarchy. I tend to view timepieces as instruments and less as jewelry, as something very personal. It's a possession that displays your taste, your personality, and can be a kind of friend.

I believe every activity has its intricacies, and therefore demands our respect and appreciation. Consider that each individual part of a watch requires a discipline. When each of those make up an elegant whole, they multiply the effect to something beyond the sum of the parts. That is why I say that the movement is not the only sophisticated component of a fine timepiece. Believe me, if you were purchasing a fine sixties Ferrari, you would not put the same money into one of the 2+2's as you would for a 250 Berlinetta. The engines were quite similar and one was even more practical. The refined connoisseur looks for balance and proportion throughout the composition, whether it is a fine meal, a painting, an organizational structure or a timepiece.

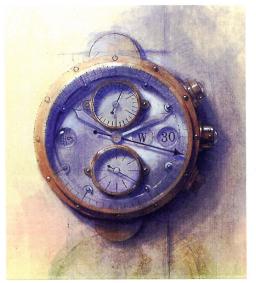

I've owned Omega, Breitling and IWC/Porsche Design chronographs and a special edition Gerald Genta made for the Italian market. It was quite interesting in that it had a bronze case with a four dials on a green face. One dial was for the date, the others were for the small seconds, 30 and 12 hour registers. What made it appropriate for the Italian market was when the case aged, the patina became green, like an antique bronze sculpture, it was the same green as the dial. Only the Italians could appreciate that. By the way, I'm wearing a 1940's Movado with complete calendar, because it was made near the time when I was born. I don't even like the case, but I'm learning about that period look by living with it. I never did care for the look until recently. Sometimes a watch comes and goes, and you discover after it goes, that you appreciate it. The thing doesn't change, you do. Perhaps I'm not typical because I have a professional interest, but I think that you can appreciate a good soup as much as a good souffle, or a well designed product regardless of price. I'd still like the Patek. Better still, I'd like to wear my own collection.