The Top Plate and Autowind Mechanism

The top plate and autowind mechanism of the Enicar 167 has a plain, workmanlike finish, not uncommon among good quality movements of the period. There is a very subtle sunburst pattern applied to the rotor and plates, topped off with a simple gilt finish. Aside from the engraving on the rotor, the number of jewels, and the movement identification, there is no other engraving on this movement. As is visible in the above scan, the movement is supplied with a eccentric-screw type micrometric regulator, identical in concept to the ETAchron regulator. Incabloc shock absorbtion is also provided.

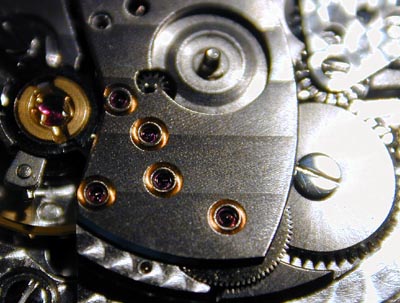

Removing the rotor reveals the final quirks of this movement:

For whatever reason, Enicar wanted to ensure that there was adequate support for the rotor in this mechanism. To that end, they placed a steel pin (a) in the center of the autowind bridge. Despite the presence of this pin, the rotor still is mounted using ball bearings, through the use of a large hollow shafted screw to secure the hub of the rotor to the pin. Clever.

The autowind bridge for bidirectional winding on this movement (b) shows the "grafted-on" nature of this system, which may have originally been adapted from a manual wind movement. While functional, the aesthetics of the adaptation by Enicar leave a bit to be desired - note in particular the fact that the "outboard" click wheel overhangs the balance and almost touches the balance cock!

The mechanism gears down the motion of the rotor to the ratchet wheel (c) with its click (d), which would look right at home in a manual wind movement. The top of the barrel (e) is visible in the part of the bridge cut-down to provide clearance for the rotor's perimeter weight. Finally, a curious manual winding works (f) with two extra intermediate wheels is visible.

When manually wound, this mechanism translates the rotation of the stem from the keyless works to the crown wheel (g). Torque then flows via the first intermediate wheel, which is held in place literally by a dent in the cover (h) and a spring (j). Finally, the motion gets translated to the second intermediate wheel (k) and then into the ratchet wheel (c). What on earth...?

The key to this mystery is understanding what happens when the watch is being automatically wound: the autowind mechanism causes the ratchet wheel (c) to move via a completely independent set of wheels. However, the second intermediate wheel (k) is still engaged to the ratchet wheel...which would normally mean that the motion would be transfered at least back to the clutch in the keyless works. This would be an unnecessary load on the autowind system, and needs to be addressed.

To this end, the first intermediate wheel and its spring pull double duty by acting as a clutch for the manual wind system - when backdriven by (k), the "floating" first intermediate wheel recoils against spring (j) while disengaging its teeth from the crown wheel (g).

Quirky. But to be fair, all automatic winding mechanisms must decouple the crown wheel by some means. However, most watches usually either hide this mechanism under a plate somewhere, or incorporate a somewhat more elegant system - this design reinforces the notion that the automatic winding system is "tacked-on".

While this system does work, the floating nature of the first intermediate wheel means that there is potential for excess wear on this wheel, especially if all the teeth in this mechanism are not fully engaged when the crown is turned. Although the potential for wear is probably minimized by the use of polished steel in these positions, this design underscores the care which should always be exercised when winding any manual wind movement.

Enter Chronoswiss

Within a few years after this watch was manufactured, the Enicar watch company ceased production. During the early 1980s, Gerd-Rüdiger Lang of Heuer struck out on his own and established Chronoswiss, a company founded to keep traditional mechanical watchmaking alive. To this end, he bought up remaining production of movements and parts at several companies, including as it turns out Enicar's calibre 165 series automatic movement. Many of his first watches were actually leftover finished movements which were sold with newly designed cases and dials.

As his company became more established, Herr Lang introduced the original Regulateur, which was the first series (albeit a limited edition) wristwatch to be made with a "regulator" dial. The dials were inspired by astronomical observatory clocks, which moved the hour hand off-center to ensure that the seconds subdial would never be obscured by the hour hand. This original series was equipped with a manual wind movement, but soon there was demand for an unlimited automatic version. In stepped the Enicar movement, with a modified motion works to produce the off-center hour.

Clearly the decoration given to the Chronoswiss version of this movement far surpasses the standard Enicar factory finish. Geneva stripes and perlage of different sizes take the place of subtle sunburst pattern with matte-gilding. In addition, the ratchet wheel has been given polished beveled teeth. However, Herr Lang did not stop there - he has replaced the bidirectional automatic winding system with a completely new unidirectional design, and in the process has increased the number of jewels from 24 to 29.

Here, the autowind system is shown with the rotor removed. Although I chickened out of disassembling the unfamiliar autowinding system, it is clear from the jewel layout that the system is completely different from the original Enicar design. Although the jewels appear to be contained in pressed in chatons as in the manual wind Orea movement, they are not; these are merely guilded engraved sinks around each of the jewels. Note that the new layout also requires relocating the click for the ratchet wheel to the opposite side of its original location.

In this scan, it is also apparent that the original de-clutching mechanism for the manual wind train was retained without significant alteration.

While some of the unusual features of this movement have been eliminated with the removal of the day-date train, Chronoswiss has added its own strangeness to the mix in compensation: Chronoswiss prides itself on making each case custom fit the movement, with no movement holder. What that implies for this and other Chronoswiss watches is, in order for it to be decased, the movement and dial must come out of the dial-side of the case. This in turn means that the bezel must be removed before decasing. No big deal for the factory service center, but it certainly adds to the complexity for the independent watchmaker who must figure out how to remove the coin-edge bezel to extract the movement.

Quirky.

Concluding Thoughts

The styling of the Enicar Sherpa Super Dive was clearly a product of its time, but at the same time has enough flair that it still looks cool today. While I doubt that it was the inspiration, the IWC Deep One incorporates color and a rotating bezel under glass in a manner quite reminescient of the Enicar. Despite the looks, and some good features like the bayonet style back and the shock mounted movement, there are several flaws in the design which should have received more consideration. Perhaps the most expensive design change would have been to incorporate a more conventional date quickset mechanism, as the one implemented is not at all very user friendly.

The Enicar 165 series automatic itself is a good basic design, and certainly is worthy of its revival in the Chronoswiss. Despite this fact, the movement's design is not particularly elegant; even in Chronoswiss guise the automatic winding mechanism still has a tacked-on look about it.

Nevertheless, as time lends new perspectives on things, we all can recognize that manufacture movements like the Enicar aren't very common these days. I do find it ironic that the movement which powered That 70s Watch has been reinvented as a model of traditional watchmaking in the Chronoswiss. Perhaps this mirrors the lives of the young cats of the "Me" generation who are now the cornerstones of their communities...

All Rights Reserved