There are precious few people who can properly understand the excitement I felt when Philippe Dufour agreed to allow me to visit him in his workshop and undoubtedly most of them are TimeZone regulars. It seems only fitting then that I should share with the TZ community my impressions of the meeting and the fact that Hans Zbinden accompanied me makes it downright compulsory. Of course, meeting Hans was quite a treat in itself. Hans is part of the heart and soul of the TimeZone community and has been around here for as long as anyone (as best I can figure). You can really get to feel like you know the regulars that you read from day to day on TZ and I knew Hans to be educated, tasteful, patient with newbies, diplomatic and remarkably well-informed (thanks to his industry spies). He proved to be all of that and more in person as well. He was extremely generous with his time and knowledge of Switzerland (he lives in Zurich) while we corresponded by e-mail prior to my visit and was clearly as excited as I was to meet Mr. Dufour in the little Bethlehem of watchmaking: the Valley de Joux. I won't bother to elaborate on the masterpieces that Mr. Dufour creates as Peter Chong's excellent article on the subject serves as reference. His watches have also been featured in Horological Times and International Wrist Watch (recent issue #42 having a detailed explanation of the differential used in the Duality). Suffice it to say that I consider him to be one of the greatest living watchmakers, the profession to which I aspire. My girlfriend, Dawn, accompanied us as well and was kind enough to take many digital photos during our trip.

There are precious few people who can properly understand the excitement I felt when Philippe Dufour agreed to allow me to visit him in his workshop and undoubtedly most of them are TimeZone regulars. It seems only fitting then that I should share with the TZ community my impressions of the meeting and the fact that Hans Zbinden accompanied me makes it downright compulsory. Of course, meeting Hans was quite a treat in itself. Hans is part of the heart and soul of the TimeZone community and has been around here for as long as anyone (as best I can figure). You can really get to feel like you know the regulars that you read from day to day on TZ and I knew Hans to be educated, tasteful, patient with newbies, diplomatic and remarkably well-informed (thanks to his industry spies). He proved to be all of that and more in person as well. He was extremely generous with his time and knowledge of Switzerland (he lives in Zurich) while we corresponded by e-mail prior to my visit and was clearly as excited as I was to meet Mr. Dufour in the little Bethlehem of watchmaking: the Valley de Joux. I won't bother to elaborate on the masterpieces that Mr. Dufour creates as Peter Chong's excellent article on the subject serves as reference. His watches have also been featured in Horological Times and International Wrist Watch (recent issue #42 having a detailed explanation of the differential used in the Duality). Suffice it to say that I consider him to be one of the greatest living watchmakers, the profession to which I aspire. My girlfriend, Dawn, accompanied us as well and was kind enough to take many digital photos during our trip.

I was very much looking forward to meeting John, knowing him to be not only a watch fanatic with great technical knowledge but also a fellow guitarist, wine lover and talented Flash-programmer. When he first wrote to me that he and Dawn were coming to Switzerland, I immediately suggested getting together in Geneva, without knowing that a meeting with Philippe Dufour was being planned. We met for the first time on Saturday and spent a fun day and evening talking, photographing, eating, drinking and visiting Geneva's many watch-shops. One highlight was certainly when the salesclerk at the Patek Philippe shop brought out a Ref. 3974 perpetual calendar repeater. At first, neither John or I dared to touch this 540,000 franc dream machine. Dawn had no such qualms however and even started fiddling with the repeater slide. Seeing this, we quickly snatched it away from her and only gave it back when the staff started exchanging nervous glances.

I was very much looking forward to meeting John, knowing him to be not only a watch fanatic with great technical knowledge but also a fellow guitarist, wine lover and talented Flash-programmer. When he first wrote to me that he and Dawn were coming to Switzerland, I immediately suggested getting together in Geneva, without knowing that a meeting with Philippe Dufour was being planned. We met for the first time on Saturday and spent a fun day and evening talking, photographing, eating, drinking and visiting Geneva's many watch-shops. One highlight was certainly when the salesclerk at the Patek Philippe shop brought out a Ref. 3974 perpetual calendar repeater. At first, neither John or I dared to touch this 540,000 franc dream machine. Dawn had no such qualms however and even started fiddling with the repeater slide. Seeing this, we quickly snatched it away from her and only gave it back when the staff started exchanging nervous glances.

Dawn and I picked Hans up a little after 10 am on Sunday, August 20th in front of the SwissHotel Metropole on the Rue Quai General. We packed his suitcases (along with ours) into our red, rented Nissan Micra and were on our way. We drove aimlessly around Geneva for 15 minutes or so with Hans continually trying to get us to "Toutes Directions" while I stubbornly resisted. Somehow we made our way back to the train station where a truce was formed and a map was purchased. You might think a good map is all that is necessary for a speedy and safe journey but I'll wager that you've never tried to navigate the mountain roads of Switzerland. To our credit I believe we only back-tracked 4 or 5 times (on the way there that is) and were well served by Hans' proclamation "as long as we're going up, we're OK". We called Philippe from the road on Hans' cel phone to tell him how miserably late we were going to be but weren't clever enough at that time to ask for detailed directions once we got to Le Sentier. That was the last time we would have a mobile signal.

I'm sure John and Dawn would never have asked me to join them if they had known what a miserable navigator I am and how completely alien I was to the region. Although I have lived most of my life in Switzerland, I had never, at least knowingly, been in the the Vallee de Joux before. I'm a die-hard city-slicker and avoid the countryside as best as I can but this area is really as picture perfect as John describes below. Of course, being the tourists we were, we had to stop the car at an incredibly steep and dangerous brink for some cow pictures. After all, these are the ones that provide the milk for the famous Swiss chocolate.

We finally descended into the beautiful Valley de Joux shortly before noon (we had been shooting for an 11 am meeting) and were awestruck by the postcard perfect caricature of Switzerland that stretched before us. The mountains were a luxurious green punctuated by grey rocky summits, the lake was a beautiful sparkling blue and the cows were brown with white spots and had big bells around their necks. Hans and I were a little giddy as we drove past Blancpain, Audemars Piguet, Kif, Frederic Piguet and Jaeger Le Coultre. According to Philippe's e-mail to me, JLC meant we were getting close. And sure enough, one of the little (and uncommon) road signs told us we had entered Le Solliat, a little hiccup of a village after the surprisingly large (for way up in the Swiss backcountry) Le Sentier. Once we located Mr. Dufour's street a whole other comedy of errors ensued as we tried to track down the address he had given us. Everyone in town knew Mr. Dufour but they all had different opinions about where he lived. Hans (the closest to a French speaker amongst us) was having a heck of a time just deciphering their varied opinions. We finally found a number 4 (his address) and parked the car. We were unfortunately on the wrong street by that point but the kind lady at that address said that not only was his workshop just down the street but that we could leave our car where it was for the afternoon.

We finally descended into the beautiful Valley de Joux shortly before noon (we had been shooting for an 11 am meeting) and were awestruck by the postcard perfect caricature of Switzerland that stretched before us. The mountains were a luxurious green punctuated by grey rocky summits, the lake was a beautiful sparkling blue and the cows were brown with white spots and had big bells around their necks. Hans and I were a little giddy as we drove past Blancpain, Audemars Piguet, Kif, Frederic Piguet and Jaeger Le Coultre. According to Philippe's e-mail to me, JLC meant we were getting close. And sure enough, one of the little (and uncommon) road signs told us we had entered Le Solliat, a little hiccup of a village after the surprisingly large (for way up in the Swiss backcountry) Le Sentier. Once we located Mr. Dufour's street a whole other comedy of errors ensued as we tried to track down the address he had given us. Everyone in town knew Mr. Dufour but they all had different opinions about where he lived. Hans (the closest to a French speaker amongst us) was having a heck of a time just deciphering their varied opinions. We finally found a number 4 (his address) and parked the car. We were unfortunately on the wrong street by that point but the kind lady at that address said that not only was his workshop just down the street but that we could leave our car where it was for the afternoon.

I once again had to regret that I spent most of my many years of mandatory French lessons doodling on my textbooks, but I still think the locals were just having fun with us. These mountain people have an offbeat sense of humor and take great joy in leading around a bunch of confused tourists by the nose.

Philippe Dufour's workshop resides in what was once the local schoolhouse. His daughters attended classes there, and the playground is still apparent in the front yard where it overlooks the cheesery (is that a word?) across the street. He greeted us at the door and showed us in. My impression was that he is a man of indeterminate age. His hair is completely white and his teeth are stained from pipe smoking but his eyes were particularly keen and his face and manners were very youthful as well. He was wearing blue jeans and a white short-sleeved shirt and had a pipe in his hand at almost every moment. His English started off as quite adequate but became comfortable and confident as he spoke with us more. He showed us into his spacious but thoroughly stocked workshop while we tried not to stammer too foolishly. I presented him with the California Zinfandel (a '96 Biale as I recall) Hans and I had brought for him and he thanked us genuinely (actually, it was purely John's gift, I ate the chocolate I bought for Philippe the night before). He then proceeded to tell us about his upcoming trip to Japan where he would exhibit his watches in the first retail store to carry them. He was a bit nervous as he only had two watches to show and needed to work out what kind of pictures and diagrams might make the best use of the ample display space the shop had provided for him. The Japanese audience, he informed us and Hans concurred, is particularly interested in the technical details and diagrams and would study whatever was presented them with great scrutiny. He thought that he would also bring a few hand tools and watch parts to round out the displays.

Philippe Dufour's workshop resides in what was once the local schoolhouse. His daughters attended classes there, and the playground is still apparent in the front yard where it overlooks the cheesery (is that a word?) across the street. He greeted us at the door and showed us in. My impression was that he is a man of indeterminate age. His hair is completely white and his teeth are stained from pipe smoking but his eyes were particularly keen and his face and manners were very youthful as well. He was wearing blue jeans and a white short-sleeved shirt and had a pipe in his hand at almost every moment. His English started off as quite adequate but became comfortable and confident as he spoke with us more. He showed us into his spacious but thoroughly stocked workshop while we tried not to stammer too foolishly. I presented him with the California Zinfandel (a '96 Biale as I recall) Hans and I had brought for him and he thanked us genuinely (actually, it was purely John's gift, I ate the chocolate I bought for Philippe the night before). He then proceeded to tell us about his upcoming trip to Japan where he would exhibit his watches in the first retail store to carry them. He was a bit nervous as he only had two watches to show and needed to work out what kind of pictures and diagrams might make the best use of the ample display space the shop had provided for him. The Japanese audience, he informed us and Hans concurred, is particularly interested in the technical details and diagrams and would study whatever was presented them with great scrutiny. He thought that he would also bring a few hand tools and watch parts to round out the displays.

I've been collecting Japanese watch magazines for a few years and even though I can't read them I'm always impressed with the rare material they find to show. The Omega Speedmaster book (which was originally a Japanese publication) is a perfect example. I jokingly suggested that Philippe bring over his entire workshop to Tokyo and apparently that's exactly what his partners there would have liked as well, no detail is unimportant to the Japanese watch lover.

At some point one of us mentioned the Simplicity that he was wearing and he said, "Ah yes, finally I've made a watch I can afford to wear". Initially I thought this was a conceit, but later realized it had some truth to it as well. Even though he is to my mind one of the more famous watchmakers around and produces watches that are fabulously expensive by most standards, he does not seem to be a particularly wealthy man. He has been able to put his daughters through school and lives a comfortable (albeit hardworking) life, but he has not sold so many watches that he could easily retire. He reminded us that when he is not actually making and selling a watch (when he is developing a new model for instance), he is not making any money whatsoever, and that these periods can last for many months. Then when he sells a watch finally, he pays his accumulated bills and hopefully has a little left over. He told us that it took him approximately 2000 hours to make a Grande and Petite Sonnerie Minute Repeater wristwatch but that he was not sure yet how many hours a Simplicity would take. He had only made five so far and it was still more or less in the prototype phase. He also confessed that his work had been set back a great deal by the recent loss of his assistant. We started to discuss his first watches (grand and petite sonnerie minute repeater pocket watches) when he suggested we adjourn for lunch.

At some point one of us mentioned the Simplicity that he was wearing and he said, "Ah yes, finally I've made a watch I can afford to wear". Initially I thought this was a conceit, but later realized it had some truth to it as well. Even though he is to my mind one of the more famous watchmakers around and produces watches that are fabulously expensive by most standards, he does not seem to be a particularly wealthy man. He has been able to put his daughters through school and lives a comfortable (albeit hardworking) life, but he has not sold so many watches that he could easily retire. He reminded us that when he is not actually making and selling a watch (when he is developing a new model for instance), he is not making any money whatsoever, and that these periods can last for many months. Then when he sells a watch finally, he pays his accumulated bills and hopefully has a little left over. He told us that it took him approximately 2000 hours to make a Grande and Petite Sonnerie Minute Repeater wristwatch but that he was not sure yet how many hours a Simplicity would take. He had only made five so far and it was still more or less in the prototype phase. He also confessed that his work had been set back a great deal by the recent loss of his assistant. We started to discuss his first watches (grand and petite sonnerie minute repeater pocket watches) when he suggested we adjourn for lunch.

We dined in a nearby restaurant where Philippe's wife and daughter and her boyfriend joined us. The meal was exquisite and accompanied by some delightful wine and conversation. Most of the talk focused on the business side of watchmaking and Mr. Dufour's strong opinions on the state of the Swiss industry. He highly values his hard-earned independence and used three other contemporary watchmakers to illustrate what can happen when one takes on investors. On one occasion, the watchmaker became quite financially successful while compromising on the quality of his entry level products to increase profits. The other two watchmakers had also been forced to compromise on the quality of their watches (to satisfy the bottom line), but with far less personal success. In one instance the founding watchmaker was forced to sell off all of his shares to his investors during hard financial times and was now merely an employee of the company that bears his name. Philippe's past dealings with one of Hans' favorite brands, Audemars Piguet, had tainted his opinion of them but he confessed that they were no worse than any other major Swiss watch house: businessmen more concerned with making money than making the best watches they can. Of investors he said "the first year they are lovers of watches, the second year they are lovers of money". It is for this reason that he will never work for another watch company again. He said he would rather sweep the streets.

We dined in a nearby restaurant where Philippe's wife and daughter and her boyfriend joined us. The meal was exquisite and accompanied by some delightful wine and conversation. Most of the talk focused on the business side of watchmaking and Mr. Dufour's strong opinions on the state of the Swiss industry. He highly values his hard-earned independence and used three other contemporary watchmakers to illustrate what can happen when one takes on investors. On one occasion, the watchmaker became quite financially successful while compromising on the quality of his entry level products to increase profits. The other two watchmakers had also been forced to compromise on the quality of their watches (to satisfy the bottom line), but with far less personal success. In one instance the founding watchmaker was forced to sell off all of his shares to his investors during hard financial times and was now merely an employee of the company that bears his name. Philippe's past dealings with one of Hans' favorite brands, Audemars Piguet, had tainted his opinion of them but he confessed that they were no worse than any other major Swiss watch house: businessmen more concerned with making money than making the best watches they can. Of investors he said "the first year they are lovers of watches, the second year they are lovers of money". It is for this reason that he will never work for another watch company again. He said he would rather sweep the streets.

Philippe told us a story about five Grande Sonnerie pocket watches he made and how two of them wound up broken. One was to be brought to an exhibition in nearby Geneva - not packed up in a box - but in the pocket of a watch company executive - between key chain and cellular phone, ouch ! In our talk it became clear that many of the independent watchmakers are overwhelmed by the business side of their work and Philippe showed great admiration for Frank Muller's success and business smarts. As a founder of the AHCI, he's a good friend of Daniel Roth and George Daniels. The three meet up once a year and go for what Philippe called the world's best cheese fondue in a restaurant close by. Both John and I were blown away by the imagination of what kind of fascinating talks these three gentlemen would hold.

I did manage to sneak in a few technical questions in between the industry discussions. I sought his opinion on the co-axial escapement and he said that it was of great interest and that George Daniels was a close friend. He did express the misgiving I've heard a number of times from other watchmakers though. Namely that the major goal (as he saw it) of the escapement was to eliminate the need for lubrication and yet Omega had decided to lubricate it. He still thought it was a great innovation and one worthy of watching closely. On the subject of overcoils he said that he uses them in all of his watches and gave Hans and me a closer look at the Simplicity he was wearing (number 00) and it's display back. In person the piece was clearly of a higher level of execution and finish than any watch I've ever had the privilege of seeing. All of its components were in complete harmony and had an elegance and, well, simplicity that was truly stunning. I asked him about the highly polished and elaborately shaped click spring (actually a click and spring in one piece) and he said that was the traditional way to make one even though it was more expensive and time consuming. On that point he maintained that his work is entirely based in tradition. Even the Duality differential itself is an old design that has been transformed from an experimental pocket watch assignment given in Watchmaking School. He lamented the utter lack of innovation in the Swiss watchmaking industry outside of the "complication cocktails" that all the big companies were coming out with. In regards to traditional watchmaking, he said, "the Germans [Lange] have surpassed us [the Swiss]" and called the Datograph "perfect" in every detail. He had hoped Patek's 10 Day movement would take back the crown of haute horology, but after much time spent examining the design (in pictures mostly), he had found several areas where corners had been cut.

I did manage to sneak in a few technical questions in between the industry discussions. I sought his opinion on the co-axial escapement and he said that it was of great interest and that George Daniels was a close friend. He did express the misgiving I've heard a number of times from other watchmakers though. Namely that the major goal (as he saw it) of the escapement was to eliminate the need for lubrication and yet Omega had decided to lubricate it. He still thought it was a great innovation and one worthy of watching closely. On the subject of overcoils he said that he uses them in all of his watches and gave Hans and me a closer look at the Simplicity he was wearing (number 00) and it's display back. In person the piece was clearly of a higher level of execution and finish than any watch I've ever had the privilege of seeing. All of its components were in complete harmony and had an elegance and, well, simplicity that was truly stunning. I asked him about the highly polished and elaborately shaped click spring (actually a click and spring in one piece) and he said that was the traditional way to make one even though it was more expensive and time consuming. On that point he maintained that his work is entirely based in tradition. Even the Duality differential itself is an old design that has been transformed from an experimental pocket watch assignment given in Watchmaking School. He lamented the utter lack of innovation in the Swiss watchmaking industry outside of the "complication cocktails" that all the big companies were coming out with. In regards to traditional watchmaking, he said, "the Germans [Lange] have surpassed us [the Swiss]" and called the Datograph "perfect" in every detail. He had hoped Patek's 10 Day movement would take back the crown of haute horology, but after much time spent examining the design (in pictures mostly), he had found several areas where corners had been cut.

(click thumbnail for larger picture)

While John was talking movements, I chatted with Madame Dufour who I think takes care of the business side of things. Before starting out as an independent watchmaker in 1978, the couple spent several years abroad in London and the Virgin Islands where Philippe worked as a repairman for Jaeger LeCoultre. She also told the story of her oldest daughter who never showed much interest in her father's work and then suddenly decided to learn the watchmaking trade herself. She's now working for Breguet and Philippe still can't believe it and is as proud as only a father can be.

We asked him about the "Resonance" by his fellow AHCI member F.P. Journe and he relayed a funny story from Basel last year. An interested observer was getting some linguistic assistance from Mr. Dufour in asking how the Resonance works (evidently Mr. Journe speaks little to no English). Mr. Journe's response was "I don't know, but it does." We all shared an enthusiasm for the work of another AHCI member, Andreas Strehler, who Philippe said he hoped would achieve the success that he deserves.

After a delicious meal of chanterelle mushrooms in cream sauce followed by lamb fillets and a suptuous dessert, he ordered us each a glass of Gentiane. Gentiane is a spirit made from the root of a locally grown plant, the wood of which Mr. Dufour uses for certain polishing procedures as well. It is served with a sugar cube to be dipped into the liquor and has a fiery, minty bite and a strong herbaceous quality. Remembering that I had to navigate the mountainous roads back to Geneva later and that I had already had a few glasses of wine, I stopped short of finishing mine.

After a delicious meal of chanterelle mushrooms in cream sauce followed by lamb fillets and a suptuous dessert, he ordered us each a glass of Gentiane. Gentiane is a spirit made from the root of a locally grown plant, the wood of which Mr. Dufour uses for certain polishing procedures as well. It is served with a sugar cube to be dipped into the liquor and has a fiery, minty bite and a strong herbaceous quality. Remembering that I had to navigate the mountainous roads back to Geneva later and that I had already had a few glasses of wine, I stopped short of finishing mine.

I only had a train to catch so I finished my glass of Gentiane, to the effect that I was close to ordering a Simplicity right on the spot. The urge became even stronger when Philippe mentioned that a slightly larger version in a steel case was planned. Thankfully, Philippe doesn't take credit cards so I was spared financial ruin.

His wife and daughter had by that point bid us farewell and shortly we returned to his workshop for more technical information than we could properly grasp. I was surprised when, on the way there, he told us that he is the game warden for the wooded area behind Le Solliat. He is a busy man but certainly not one-dimensional.

His wife and daughter had by that point bid us farewell and shortly we returned to his workshop for more technical information than we could properly grasp. I was surprised when, on the way there, he told us that he is the game warden for the wooded area behind Le Solliat. He is a busy man but certainly not one-dimensional.

His workshop is probably 12 meters long by 8 meters wide and has numerous stations in it for performing various operations. Just in front of the door as you walk in there are two lathes, one slightly larger than the other. His primary lathe (the smaller one) is a Schaublin 70(mm). He insists that the Schaublin 70 is the best watchmaking lathe there is and that I should try to get one eventually. I said, "I suppose they cost somewhere upwards of $20,000." To which he replied, "Yes, they do, but they're worth it." Of course he has all kinds of attachments for it that would increase the cost significantly.

Being absolutely incompetent with any type of tools, I was astounded to hear that one could basically make an entire watch from scratch with such a lathe and its attachments, it can do virtually any job that's required but for some, there are specialized machines that do the job quicker and better.

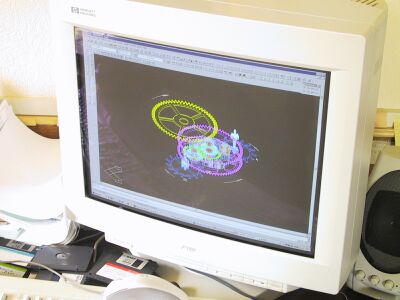

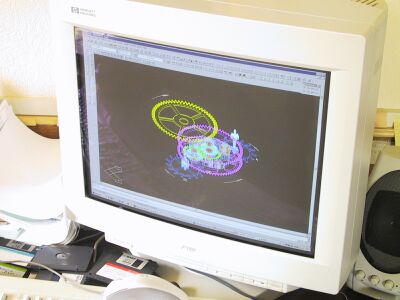

In the back of his workshop is a high precision drill press with computer controlled adjustments for accuracy to 6 decimal places. He told us that when he first started using a computer he was quite suspicious of its accuracy. Being accustomed to the fact that even the most precise measuring devices can give a slightly different reading before and after lunch for instance (due to variations in temperature, humidity, etc), he took the same measurement with the computer controlled device twice (at different times) and couldn't believe that it gave him the same exact number ("to 6 decimal places!" he exclaimed). He finally convinced himself that the computer was not cheating somehow and began using computers for a variety of applications but most notably for the actual movement design itself. He has two computers set up in his workshop as well as an older machine (the one that the duality was designed on) that is not currently in use. He taught himself Autocad at one point and now uses it for many aspects of the design including the production of templates for individual parts.

Teaching oneself Autocad is quite a task in itself but Philippe had to do the whole thing in total secrecy. He was then working on the world's first Grande Sonnerie wrist watch and didn't want anybody to know about it and was scared that if local technicians came by and saw what he was doing, the entire valley would know about it within the hour.

Teaching oneself Autocad is quite a task in itself but Philippe had to do the whole thing in total secrecy. He was then working on the world's first Grande Sonnerie wrist watch and didn't want anybody to know about it and was scared that if local technicians came by and saw what he was doing, the entire valley would know about it within the hour.

In the middle of his workshop are ten or twelve machines that do everything from cutting gears and polishing pinion leaves to creating Geneva stripes. Hans and I were both a little surprised to find that Geneva stripes have no noticeable texture on the plate. Philippe said that some more grossly produced decorative stripes have perceptible ridges but that traditionally made Geneva stripes are smooth to the touch. Many of the specialized machines in his workshop are no longer being produced and can only be found with some luck and persistence. In one instance however, his luck had found him a useful, complicated and unavailable machine for only 5 Swiss francs, the value of the raw steel sold as scrap. Near the door of the workshop he has an optical comparitor that he uses to check the final shape of different parts in comparison to the highly magnified computer drawings. This is particularly important after polishing the pinion leaves where a few more seconds of polishing can be problematic.

He described to us in detail much of the initial stages of creating a watch starting with a bar of German silver. It would be easier to start with a plate (of the desired thickness) but the grain of the silver would then be perpendicular to most of the drilling procedures and this can create variations in the angles and shapes of the holes. On the issue of German silver and its handling he was particularly in awe of Lange's ability to use it in an untreated form. Any contact with the silver can stain it and sometimes a stain can simply manifest from within the metal itself. For these reasons he plates his with rhodium before the final finish is applied. After cutting the mainplate to size he drills three aligning holes in it that will then be used as reference points for all the other drilling and milling procedures. In this way he avoids the extra holes that can sometimes be left-over in a mass-produced movement plate. He then drills the many holes (46 for the Simplicity alone) and mills the many different levels that are ultimately needed. On the smaller pieces, he usually drills the holes and does some milling before sending them out for spark erosion cutting. Many pieces cannot be cut precisely this way because the erosion machine would burn through the very thin segments of delicate springs (many of which are found in repeaters and striking watches). For larger work though, it can achieve an accuracy that is unattainable with more traditional techniques. It might be surprising to some that Mr. Dufour has work performed elsewhere but he is always more conscious of the quality of the work rather than maintaining some ideal of handcraftsmanship (evidenced also by his use of computers). He also doesn't make the crystals, cases, hands, dials, jewels, hairsprings, mainsprings or, you guessed it, the screws in his watches. He attempted to buy gyromax balances elsewhere but was unable to. Instead he decided to make his own adjustable mass version of a screwed balance, which he was pleased was even more attractive while being more or less equally effective.

He described to us in detail much of the initial stages of creating a watch starting with a bar of German silver. It would be easier to start with a plate (of the desired thickness) but the grain of the silver would then be perpendicular to most of the drilling procedures and this can create variations in the angles and shapes of the holes. On the issue of German silver and its handling he was particularly in awe of Lange's ability to use it in an untreated form. Any contact with the silver can stain it and sometimes a stain can simply manifest from within the metal itself. For these reasons he plates his with rhodium before the final finish is applied. After cutting the mainplate to size he drills three aligning holes in it that will then be used as reference points for all the other drilling and milling procedures. In this way he avoids the extra holes that can sometimes be left-over in a mass-produced movement plate. He then drills the many holes (46 for the Simplicity alone) and mills the many different levels that are ultimately needed. On the smaller pieces, he usually drills the holes and does some milling before sending them out for spark erosion cutting. Many pieces cannot be cut precisely this way because the erosion machine would burn through the very thin segments of delicate springs (many of which are found in repeaters and striking watches). For larger work though, it can achieve an accuracy that is unattainable with more traditional techniques. It might be surprising to some that Mr. Dufour has work performed elsewhere but he is always more conscious of the quality of the work rather than maintaining some ideal of handcraftsmanship (evidenced also by his use of computers). He also doesn't make the crystals, cases, hands, dials, jewels, hairsprings, mainsprings or, you guessed it, the screws in his watches. He attempted to buy gyromax balances elsewhere but was unable to. Instead he decided to make his own adjustable mass version of a screwed balance, which he was pleased was even more attractive while being more or less equally effective.

I didn't realize that all plates have holes in them that are used only for alignment during drilling. Philippe's plates have three of these non-functional holes but he mentioned that many movements were full of them almost like Swiss cheese. While he has the machines and the knowledge to make virtually every part of the movement himself, the Simplicity will be made in a large enough series to merit a few raw parts being made outside. For example, he ordered a number of small, flat disks out of which he cuts the wheels. The prototypes of the watch are fit with a NOS gyromax balance, which he wanted to have re-made by ETA for the series production. They refused his request before he showed them a written permission by the holder of the patent (guess who) - which was promptly denied. As sophisticated and worldly as the Swiss industry likes to present itself, its little intrigues, dramas and jealousy would make for a great soap opera.

I didn't realize that all plates have holes in them that are used only for alignment during drilling. Philippe's plates have three of these non-functional holes but he mentioned that many movements were full of them almost like Swiss cheese. While he has the machines and the knowledge to make virtually every part of the movement himself, the Simplicity will be made in a large enough series to merit a few raw parts being made outside. For example, he ordered a number of small, flat disks out of which he cuts the wheels. The prototypes of the watch are fit with a NOS gyromax balance, which he wanted to have re-made by ETA for the series production. They refused his request before he showed them a written permission by the holder of the patent (guess who) - which was promptly denied. As sophisticated and worldly as the Swiss industry likes to present itself, its little intrigues, dramas and jealousy would make for a great soap opera.

As the time for our departure approached Dawn became a little fidgety and practically had to drag us from the room. Philippe was clearly not done talking and God knows Hans and I could have spent another day or two there, but we did have a train to catch. One of the last questions that I asked him was about the torque applied to the two different escapements in the Duality and if they demonstrated variations in amplitude because of it. He said that he combatted this by making the lower fourth wheel (where some of the hardware for the differential is mounted) lighter than the upper fourth wheel. I didn't get to ask him to elaborate on it further though as our train was leaving in a little over an hour.

My only regret about our visit was that we didn't stay until he kicked us out and to hell with our train schedule. Surely another hour or two of conversation would've been worth sleeping in the woods in the Valley de Joux (although Philippe would have probably run us off, game wardens don't like riff-raff sleeping in the woods), or certainly spending another night in Geneva. I'll have to take him up on his offer to have us back and feed us some of the cheese fondue the Swiss are famous for. Maybe next time I'll think to write down all the questions I want to ask him.

(click thumbnail for larger picture)

Before my visit with him I was of the opinion that he is one of the top two or three watchmakers living today. I won't take into account all of the faceless geniuses that are slaving away without any recognition because I can't know anything about them, but of the Masters with which I am familiar, he has few peers. Upon meeting him I was delighted to find that he is also a charming and witty man and a most gracious host. After discussing with him the difficulties involved in creating and selling his own watches, without financial support or compromise, as well as seeing the immaculate care that he insists on taking with each piece as it is made, I can now honestly say that I believe his work to be unequalled. The strange completeness that his line of only three watches demonstrates (Master craftsmanship, technical innovation (of a sort), and simplicity) is perfectly matched by his refined aesthetic vision and commitment to excellence in execution. He is a most suitable role model for an aspiring watchmaker in these interesting times in which we live.

I have nothing to add to John's final statement except that I too would have gladly camped outside in the valley for another fascinating day at Philippe's workshop, even though the cows would have made me worry. My sincere thanks to Philippe, John and Dawn for this unforgettable weekend.

There are precious few people who can properly understand the excitement I felt when Philippe Dufour agreed to allow me to visit him in his workshop and undoubtedly most of them are TimeZone regulars. It seems only fitting then that I should share with the TZ community my impressions of the meeting and the fact that Hans Zbinden accompanied me makes it downright compulsory. Of course, meeting Hans was quite a treat in itself. Hans is part of the heart and soul of the TimeZone community and has been around here for as long as anyone (as best I can figure). You can really get to feel like you know the regulars that you read from day to day on TZ and I knew Hans to be educated, tasteful, patient with newbies, diplomatic and remarkably well-informed (thanks to his industry spies). He proved to be all of that and more in person as well. He was extremely generous with his time and knowledge of Switzerland (he lives in Zurich) while we corresponded by e-mail prior to my visit and was clearly as excited as I was to meet Mr. Dufour in the little Bethlehem of watchmaking: the Valley de Joux. I won't bother to elaborate on the masterpieces that Mr. Dufour creates as

There are precious few people who can properly understand the excitement I felt when Philippe Dufour agreed to allow me to visit him in his workshop and undoubtedly most of them are TimeZone regulars. It seems only fitting then that I should share with the TZ community my impressions of the meeting and the fact that Hans Zbinden accompanied me makes it downright compulsory. Of course, meeting Hans was quite a treat in itself. Hans is part of the heart and soul of the TimeZone community and has been around here for as long as anyone (as best I can figure). You can really get to feel like you know the regulars that you read from day to day on TZ and I knew Hans to be educated, tasteful, patient with newbies, diplomatic and remarkably well-informed (thanks to his industry spies). He proved to be all of that and more in person as well. He was extremely generous with his time and knowledge of Switzerland (he lives in Zurich) while we corresponded by e-mail prior to my visit and was clearly as excited as I was to meet Mr. Dufour in the little Bethlehem of watchmaking: the Valley de Joux. I won't bother to elaborate on the masterpieces that Mr. Dufour creates as  I was very much looking forward to meeting John, knowing him to be not only a watch fanatic with great technical knowledge but also a fellow guitarist, wine lover and talented Flash-programmer. When he first wrote to me that he and Dawn were coming to Switzerland, I immediately suggested getting together in Geneva, without knowing that a meeting with Philippe Dufour was being planned. We met for the first time on Saturday and spent a fun day and evening talking, photographing, eating, drinking and visiting Geneva's many watch-shops. One highlight was certainly when the salesclerk at the Patek Philippe shop brought out a Ref. 3974 perpetual calendar repeater. At first, neither John or I dared to touch this 540,000 franc dream machine. Dawn had no such qualms however and even started fiddling with the repeater slide. Seeing this, we quickly snatched it away from her and only gave it back when the staff started exchanging nervous glances.

I was very much looking forward to meeting John, knowing him to be not only a watch fanatic with great technical knowledge but also a fellow guitarist, wine lover and talented Flash-programmer. When he first wrote to me that he and Dawn were coming to Switzerland, I immediately suggested getting together in Geneva, without knowing that a meeting with Philippe Dufour was being planned. We met for the first time on Saturday and spent a fun day and evening talking, photographing, eating, drinking and visiting Geneva's many watch-shops. One highlight was certainly when the salesclerk at the Patek Philippe shop brought out a Ref. 3974 perpetual calendar repeater. At first, neither John or I dared to touch this 540,000 franc dream machine. Dawn had no such qualms however and even started fiddling with the repeater slide. Seeing this, we quickly snatched it away from her and only gave it back when the staff started exchanging nervous glances. We finally descended into the beautiful Valley de Joux shortly before noon (we had been shooting for an 11 am meeting) and were awestruck by the postcard perfect caricature of Switzerland that stretched before us. The mountains were a luxurious green punctuated by grey rocky summits, the lake was a beautiful sparkling blue and the cows were brown with white spots and had big bells around their necks. Hans and I were a little giddy as we drove past Blancpain, Audemars Piguet, Kif, Frederic Piguet and Jaeger Le Coultre. According to Philippe's e-mail to me, JLC meant we were getting close. And sure enough, one of the little (and uncommon) road signs told us we had entered Le Solliat, a little hiccup of a village after the surprisingly large (for way up in the Swiss backcountry) Le Sentier. Once we located Mr. Dufour's street a whole other comedy of errors ensued as we tried to track down the address he had given us. Everyone in town knew Mr. Dufour but they all had different opinions about where he lived. Hans (the closest to a French speaker amongst us) was having a heck of a time just deciphering their varied opinions. We finally found a number 4 (his address) and parked the car. We were unfortunately on the wrong street by that point but the kind lady at that address said that not only was his workshop just down the street but that we could leave our car where it was for the afternoon.

We finally descended into the beautiful Valley de Joux shortly before noon (we had been shooting for an 11 am meeting) and were awestruck by the postcard perfect caricature of Switzerland that stretched before us. The mountains were a luxurious green punctuated by grey rocky summits, the lake was a beautiful sparkling blue and the cows were brown with white spots and had big bells around their necks. Hans and I were a little giddy as we drove past Blancpain, Audemars Piguet, Kif, Frederic Piguet and Jaeger Le Coultre. According to Philippe's e-mail to me, JLC meant we were getting close. And sure enough, one of the little (and uncommon) road signs told us we had entered Le Solliat, a little hiccup of a village after the surprisingly large (for way up in the Swiss backcountry) Le Sentier. Once we located Mr. Dufour's street a whole other comedy of errors ensued as we tried to track down the address he had given us. Everyone in town knew Mr. Dufour but they all had different opinions about where he lived. Hans (the closest to a French speaker amongst us) was having a heck of a time just deciphering their varied opinions. We finally found a number 4 (his address) and parked the car. We were unfortunately on the wrong street by that point but the kind lady at that address said that not only was his workshop just down the street but that we could leave our car where it was for the afternoon. Philippe Dufour's workshop resides in what was once the local schoolhouse. His daughters attended classes there, and the playground is still apparent in the front yard where it overlooks the cheesery (is that a word?) across the street. He greeted us at the door and showed us in. My impression was that he is a man of indeterminate age. His hair is completely white and his teeth are stained from pipe smoking but his eyes were particularly keen and his face and manners were very youthful as well. He was wearing blue jeans and a white short-sleeved shirt and had a pipe in his hand at almost every moment. His English started off as quite adequate but became comfortable and confident as he spoke with us more. He showed us into his spacious but thoroughly stocked workshop while we tried not to stammer too foolishly. I presented him with the California Zinfandel (a '96 Biale as I recall) Hans and I had brought for him and he thanked us genuinely (actually, it was purely John's gift, I ate the chocolate I bought for Philippe the night before). He then proceeded to tell us about his upcoming trip to Japan where he would exhibit his watches in the first retail store to carry them. He was a bit nervous as he only had two watches to show and needed to work out what kind of pictures and diagrams might make the best use of the ample display space the shop had provided for him. The Japanese audience, he informed us and Hans concurred, is particularly interested in the technical details and diagrams and would study whatever was presented them with great scrutiny. He thought that he would also bring a few hand tools and watch parts to round out the displays.

Philippe Dufour's workshop resides in what was once the local schoolhouse. His daughters attended classes there, and the playground is still apparent in the front yard where it overlooks the cheesery (is that a word?) across the street. He greeted us at the door and showed us in. My impression was that he is a man of indeterminate age. His hair is completely white and his teeth are stained from pipe smoking but his eyes were particularly keen and his face and manners were very youthful as well. He was wearing blue jeans and a white short-sleeved shirt and had a pipe in his hand at almost every moment. His English started off as quite adequate but became comfortable and confident as he spoke with us more. He showed us into his spacious but thoroughly stocked workshop while we tried not to stammer too foolishly. I presented him with the California Zinfandel (a '96 Biale as I recall) Hans and I had brought for him and he thanked us genuinely (actually, it was purely John's gift, I ate the chocolate I bought for Philippe the night before). He then proceeded to tell us about his upcoming trip to Japan where he would exhibit his watches in the first retail store to carry them. He was a bit nervous as he only had two watches to show and needed to work out what kind of pictures and diagrams might make the best use of the ample display space the shop had provided for him. The Japanese audience, he informed us and Hans concurred, is particularly interested in the technical details and diagrams and would study whatever was presented them with great scrutiny. He thought that he would also bring a few hand tools and watch parts to round out the displays. At some point one of us mentioned the Simplicity that he was wearing and he said, "Ah yes, finally I've made a watch I can afford to wear". Initially I thought this was a conceit, but later realized it had some truth to it as well. Even though he is to my mind one of the more famous watchmakers around and produces watches that are fabulously expensive by most standards, he does not seem to be a particularly wealthy man. He has been able to put his daughters through school and lives a comfortable (albeit hardworking) life, but he has not sold so many watches that he could easily retire. He reminded us that when he is not actually making and selling a watch (when he is developing a new model for instance), he is not making any money whatsoever, and that these periods can last for many months. Then when he sells a watch finally, he pays his accumulated bills and hopefully has a little left over. He told us that it took him approximately 2000 hours to make a Grande and Petite Sonnerie Minute Repeater wristwatch but that he was not sure yet how many hours a Simplicity would take. He had only made five so far and it was still more or less in the prototype phase. He also confessed that his work had been set back a great deal by the recent loss of his assistant. We started to discuss his first watches (grand and petite sonnerie minute repeater pocket watches) when he suggested we adjourn for lunch.

At some point one of us mentioned the Simplicity that he was wearing and he said, "Ah yes, finally I've made a watch I can afford to wear". Initially I thought this was a conceit, but later realized it had some truth to it as well. Even though he is to my mind one of the more famous watchmakers around and produces watches that are fabulously expensive by most standards, he does not seem to be a particularly wealthy man. He has been able to put his daughters through school and lives a comfortable (albeit hardworking) life, but he has not sold so many watches that he could easily retire. He reminded us that when he is not actually making and selling a watch (when he is developing a new model for instance), he is not making any money whatsoever, and that these periods can last for many months. Then when he sells a watch finally, he pays his accumulated bills and hopefully has a little left over. He told us that it took him approximately 2000 hours to make a Grande and Petite Sonnerie Minute Repeater wristwatch but that he was not sure yet how many hours a Simplicity would take. He had only made five so far and it was still more or less in the prototype phase. He also confessed that his work had been set back a great deal by the recent loss of his assistant. We started to discuss his first watches (grand and petite sonnerie minute repeater pocket watches) when he suggested we adjourn for lunch. We dined in a nearby restaurant where Philippe's wife and daughter and her boyfriend joined us. The meal was exquisite and accompanied by some delightful wine and conversation. Most of the talk focused on the business side of watchmaking and Mr. Dufour's strong opinions on the state of the Swiss industry. He highly values his hard-earned independence and used three other contemporary watchmakers to illustrate what can happen when one takes on investors. On one occasion, the watchmaker became quite financially successful while compromising on the quality of his entry level products to increase profits. The other two watchmakers had also been forced to compromise on the quality of their watches (to satisfy the bottom line), but with far less personal success. In one instance the founding watchmaker was forced to sell off all of his shares to his investors during hard financial times and was now merely an employee of the company that bears his name. Philippe's past dealings with one of Hans' favorite brands, Audemars Piguet, had tainted his opinion of them but he confessed that they were no worse than any other major Swiss watch house: businessmen more concerned with making money than making the best watches they can. Of investors he said "the first year they are lovers of watches, the second year they are lovers of money". It is for this reason that he will never work for another watch company again. He said he would rather sweep the streets.

We dined in a nearby restaurant where Philippe's wife and daughter and her boyfriend joined us. The meal was exquisite and accompanied by some delightful wine and conversation. Most of the talk focused on the business side of watchmaking and Mr. Dufour's strong opinions on the state of the Swiss industry. He highly values his hard-earned independence and used three other contemporary watchmakers to illustrate what can happen when one takes on investors. On one occasion, the watchmaker became quite financially successful while compromising on the quality of his entry level products to increase profits. The other two watchmakers had also been forced to compromise on the quality of their watches (to satisfy the bottom line), but with far less personal success. In one instance the founding watchmaker was forced to sell off all of his shares to his investors during hard financial times and was now merely an employee of the company that bears his name. Philippe's past dealings with one of Hans' favorite brands, Audemars Piguet, had tainted his opinion of them but he confessed that they were no worse than any other major Swiss watch house: businessmen more concerned with making money than making the best watches they can. Of investors he said "the first year they are lovers of watches, the second year they are lovers of money". It is for this reason that he will never work for another watch company again. He said he would rather sweep the streets. I did manage to sneak in a few technical questions in between the industry discussions. I sought his opinion on the co-axial escapement and he said that it was of great interest and that George Daniels was a close friend. He did express the misgiving I've heard a number of times from other watchmakers though. Namely that the major goal (as he saw it) of the escapement was to eliminate the need for lubrication and yet Omega had decided to lubricate it. He still thought it was a great innovation and one worthy of watching closely. On the subject of overcoils he said that he uses them in all of his watches and gave Hans and me a closer look at the Simplicity he was wearing (number 00) and it's display back. In person the piece was clearly of a higher level of execution and finish than any watch I've ever had the privilege of seeing. All of its components were in complete harmony and had an elegance and, well, simplicity that was truly stunning. I asked him about the highly polished and elaborately shaped click spring (actually a click and spring in one piece) and he said that was the traditional way to make one even though it was more expensive and time consuming. On that point he maintained that his work is entirely based in tradition. Even the Duality differential itself is an old design that has been transformed from an experimental pocket watch assignment given in Watchmaking School. He lamented the utter lack of innovation in the Swiss watchmaking industry outside of the "complication cocktails" that all the big companies were coming out with. In regards to traditional watchmaking, he said, "the Germans [Lange] have surpassed us [the Swiss]" and called the Datograph "perfect" in every detail. He had hoped Patek's 10 Day movement would take back the crown of haute horology, but after much time spent examining the design (in pictures mostly), he had found several areas where corners had been cut.

I did manage to sneak in a few technical questions in between the industry discussions. I sought his opinion on the co-axial escapement and he said that it was of great interest and that George Daniels was a close friend. He did express the misgiving I've heard a number of times from other watchmakers though. Namely that the major goal (as he saw it) of the escapement was to eliminate the need for lubrication and yet Omega had decided to lubricate it. He still thought it was a great innovation and one worthy of watching closely. On the subject of overcoils he said that he uses them in all of his watches and gave Hans and me a closer look at the Simplicity he was wearing (number 00) and it's display back. In person the piece was clearly of a higher level of execution and finish than any watch I've ever had the privilege of seeing. All of its components were in complete harmony and had an elegance and, well, simplicity that was truly stunning. I asked him about the highly polished and elaborately shaped click spring (actually a click and spring in one piece) and he said that was the traditional way to make one even though it was more expensive and time consuming. On that point he maintained that his work is entirely based in tradition. Even the Duality differential itself is an old design that has been transformed from an experimental pocket watch assignment given in Watchmaking School. He lamented the utter lack of innovation in the Swiss watchmaking industry outside of the "complication cocktails" that all the big companies were coming out with. In regards to traditional watchmaking, he said, "the Germans [Lange] have surpassed us [the Swiss]" and called the Datograph "perfect" in every detail. He had hoped Patek's 10 Day movement would take back the crown of haute horology, but after much time spent examining the design (in pictures mostly), he had found several areas where corners had been cut.

After a delicious meal of chanterelle mushrooms in cream sauce followed by lamb fillets and a suptuous dessert, he ordered us each a glass of Gentiane. Gentiane is a spirit made from the root of a locally grown plant, the wood of which Mr. Dufour uses for certain polishing procedures as well. It is served with a sugar cube to be dipped into the liquor and has a fiery, minty bite and a strong herbaceous quality. Remembering that I had to navigate the mountainous roads back to Geneva later and that I had already had a few glasses of wine, I stopped short of finishing mine.

After a delicious meal of chanterelle mushrooms in cream sauce followed by lamb fillets and a suptuous dessert, he ordered us each a glass of Gentiane. Gentiane is a spirit made from the root of a locally grown plant, the wood of which Mr. Dufour uses for certain polishing procedures as well. It is served with a sugar cube to be dipped into the liquor and has a fiery, minty bite and a strong herbaceous quality. Remembering that I had to navigate the mountainous roads back to Geneva later and that I had already had a few glasses of wine, I stopped short of finishing mine.  His wife and daughter had by that point bid us farewell and shortly we returned to his workshop for more technical information than we could properly grasp. I was surprised when, on the way there, he told us that he is the game warden for the wooded area behind Le Solliat. He is a busy man but certainly not one-dimensional.

His wife and daughter had by that point bid us farewell and shortly we returned to his workshop for more technical information than we could properly grasp. I was surprised when, on the way there, he told us that he is the game warden for the wooded area behind Le Solliat. He is a busy man but certainly not one-dimensional.  Teaching oneself Autocad is quite a task in itself but Philippe had to do the whole thing in total secrecy. He was then working on the world's first Grande Sonnerie wrist watch and didn't want anybody to know about it and was scared that if local technicians came by and saw what he was doing, the entire valley would know about it within the hour.

Teaching oneself Autocad is quite a task in itself but Philippe had to do the whole thing in total secrecy. He was then working on the world's first Grande Sonnerie wrist watch and didn't want anybody to know about it and was scared that if local technicians came by and saw what he was doing, the entire valley would know about it within the hour. He described to us in detail much of the initial stages of creating a watch starting with a bar of German silver. It would be easier to start with a plate (of the desired thickness) but the grain of the silver would then be perpendicular to most of the drilling procedures and this can create variations in the angles and shapes of the holes. On the issue of German silver and its handling he was particularly in awe of Lange's ability to use it in an untreated form. Any contact with the silver can stain it and sometimes a stain can simply manifest from within the metal itself. For these reasons he plates his with rhodium before the final finish is applied. After cutting the mainplate to size he drills three aligning holes in it that will then be used as reference points for all the other drilling and milling procedures. In this way he avoids the extra holes that can sometimes be left-over in a mass-produced movement plate. He then drills the many holes (46 for the Simplicity alone) and mills the many different levels that are ultimately needed. On the smaller pieces, he usually drills the holes and does some milling before sending them out for spark erosion cutting. Many pieces cannot be cut precisely this way because the erosion machine would burn through the very thin segments of delicate springs (many of which are found in repeaters and striking watches). For larger work though, it can achieve an accuracy that is unattainable with more traditional techniques. It might be surprising to some that Mr. Dufour has work performed elsewhere but he is always more conscious of the quality of the work rather than maintaining some ideal of handcraftsmanship (evidenced also by his use of computers). He also doesn't make the crystals, cases, hands, dials, jewels, hairsprings, mainsprings or, you guessed it, the screws in his watches. He attempted to buy gyromax balances elsewhere but was unable to. Instead he decided to make his own adjustable mass version of a screwed balance, which he was pleased was even more attractive while being more or less equally effective.

He described to us in detail much of the initial stages of creating a watch starting with a bar of German silver. It would be easier to start with a plate (of the desired thickness) but the grain of the silver would then be perpendicular to most of the drilling procedures and this can create variations in the angles and shapes of the holes. On the issue of German silver and its handling he was particularly in awe of Lange's ability to use it in an untreated form. Any contact with the silver can stain it and sometimes a stain can simply manifest from within the metal itself. For these reasons he plates his with rhodium before the final finish is applied. After cutting the mainplate to size he drills three aligning holes in it that will then be used as reference points for all the other drilling and milling procedures. In this way he avoids the extra holes that can sometimes be left-over in a mass-produced movement plate. He then drills the many holes (46 for the Simplicity alone) and mills the many different levels that are ultimately needed. On the smaller pieces, he usually drills the holes and does some milling before sending them out for spark erosion cutting. Many pieces cannot be cut precisely this way because the erosion machine would burn through the very thin segments of delicate springs (many of which are found in repeaters and striking watches). For larger work though, it can achieve an accuracy that is unattainable with more traditional techniques. It might be surprising to some that Mr. Dufour has work performed elsewhere but he is always more conscious of the quality of the work rather than maintaining some ideal of handcraftsmanship (evidenced also by his use of computers). He also doesn't make the crystals, cases, hands, dials, jewels, hairsprings, mainsprings or, you guessed it, the screws in his watches. He attempted to buy gyromax balances elsewhere but was unable to. Instead he decided to make his own adjustable mass version of a screwed balance, which he was pleased was even more attractive while being more or less equally effective. I didn't realize that all plates have holes in them that are used only for alignment during drilling. Philippe's plates have three of these non-functional holes but he mentioned that many movements were full of them almost like Swiss cheese. While he has the machines and the knowledge to make virtually every part of the movement himself, the Simplicity will be made in a large enough series to merit a few raw parts being made outside. For example, he ordered a number of small, flat disks out of which he cuts the wheels. The prototypes of the watch are fit with a NOS gyromax balance, which he wanted to have re-made by ETA for the series production. They refused his request before he showed them a written permission by the holder of the patent (guess who) - which was promptly denied. As sophisticated and worldly as the Swiss industry likes to present itself, its little intrigues, dramas and jealousy would make for a great soap opera.

I didn't realize that all plates have holes in them that are used only for alignment during drilling. Philippe's plates have three of these non-functional holes but he mentioned that many movements were full of them almost like Swiss cheese. While he has the machines and the knowledge to make virtually every part of the movement himself, the Simplicity will be made in a large enough series to merit a few raw parts being made outside. For example, he ordered a number of small, flat disks out of which he cuts the wheels. The prototypes of the watch are fit with a NOS gyromax balance, which he wanted to have re-made by ETA for the series production. They refused his request before he showed them a written permission by the holder of the patent (guess who) - which was promptly denied. As sophisticated and worldly as the Swiss industry likes to present itself, its little intrigues, dramas and jealousy would make for a great soap opera.