Beauty, and the handwound movement...

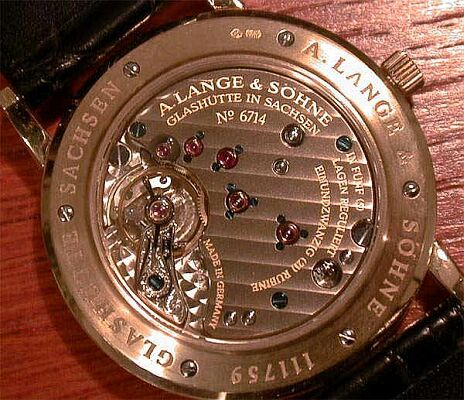

The more I look at and study watches, the more I find refined simplicity to have a growing appeal: The simplest, most elegant ultrathin automatics, and of course the time-only manually-wound movement free of superfluous complications. No doubt "haute" complications have their place within horology as paramount works of the watchmakers craft, but for most of us the world of Grande Complications, carillons, and even perpetual calendars is a closed one where we are only spectators. Indeed, we find ourselves wandering through a vast wasteland of layered modular complications that attempt to mimic in some way the mostly inaccessible works of haute horlogerie. Browse through a current glossy watch magazine and you will find a mind-numbing repetition of watches equipped with generic chronograph modules, big-date modules, power-reserve modules, jump hours, and retrograde this or that, all of which have bonded to one of the generic automatic ebauches spawned in ETA's vast cauldrons -- the Frankenstein's monsters of our age. It also seems that all but the most elite of the watchmaking masters and manufactures have converted wholly to the religion of the rotor. Nearly 600 years of hand-winding by key or crown has been supplanted by a tyranny of "automatic" winding, forcing many collectors to succumb to the Scylla of the mechanical watch revival -- the electric "automatic watch" winding appliance. Even the beauty of classical integrated complications is obscured by winding bridges more often than not. I would like to take a "time out" from all of this in the oasis of simplicity, to celebrate the purest and most essential form of the mechanical timekeeping heritage -- the handwound movement. Here are a few of those forms which for various reasons I personally find appealing. In addition to four simple handwinds (two vintage and two current), I have chosen to add two of the aforementioned classic complications which when integrated into the basic handwound calibre, not only enhance its physical beauty, but that also alter how we perceive and interact with time.  Behold Lange calibre L941.1, the challenge of Saxony to the best and brightest of Geneva and Le Brassus -- a challenge that has suceeded in winning the hearts of numerous watch enthusiasts and the respect of master watchmakers. The 3/4 plate 11''' calibre is a robust 3.2mm in thickness and bears a full 21 jewels. While just introduced in 1994, the design of this calibre represents not only an entire era of pocket watch movements, but also the first movements used in adapted wristlet watches -- like IWC's calibre 64. The luxury finish now characteristic of Lange wristwatch movements was previously reserved by the old Lange company for its foreign exports. Not only is this the finest 3/4 plate calibre in production, but also one of the finest handwinds of our time. It remains the most accessible offering in the small A. Lange & Sohne collection, used in the 1815 and as a base movement in the 1815 Auf/Ab, 1815 Moonphase, and Saxonia (my personal favourite). The L941 is the simplest, and perhaps the most lovely product of the Glashutte manufacture.  This vintage movement reflects not only the close tie between handwound pocket and wristwatch calibres, but the transition between 3/4 plate and full-bridge movements -- the most obvious clue to the latter being the press-fit chatons. IWC's calibre 83 was produced in the 1930s and 40s, and its six-bridge layout closely mirrors the IWC pocket watch calibres of the same era -- the 95 and 98. This 12 ligne, 18,000vph calibre has been produced in 15, 16, and 17 jewel variants like the one shown, and through most of its history did not have shock resistance. Incabloc was later added when the movement was redesigned for use in the Mark X military watch. Perhaps due to my background with pocket watches, I find this to be most beautiful wristwatch calibre ever manufactured by IWC. As most vintage IWC collectors and fans are focused upon later watches utilizing calibre 89 and the calibre 85 variants, calibre 83 remains in relative obscurity, largely lost to time.  Here is the face of an artifact from the end of the golden age of Genevese watchmaking: Patek Philippe's 10''' calibre 23-300. It was produced from 1956 to 1977, when at the first stirrings of the quartz revolution it was replaced with the present calibre 215. The 23-300 is one of very few movements manufactured by Patek Philippe to use both an overcoil hairspring and a free-sprung Gyromax balance, and of which it was the only 10''' handwind. It represents both the technical and artistic peak of Patek's 10 ligne handwinds, as the 27-AM 400 was the peak of their 12 lignes. The example shown above is the final evolution of this movement, calibre 23-300 PM. A "Piton Mobile," or mobile stud carrier, was added to the movement in 1970. Sadly its five-bridge form, which was characteristic of Patek's handwound calibres, was lost in the change to the 215 as was much of the classical "curved bar" shape. The advance from the 23-300's 21,600vph rate to the 215's 28,800vph was also unfortunate in my opinion. Others may disagree, but I feel that the 215 is a step down from its predecessor. In the image above, we see the pinnacle of Patek's true greatness in the craft.  Blancpain is the most controversial of the fine watchmaking houses for many reasons -- like its youth contrasted with its marketing claim of vast age, but no doubt its single greatest controversy is the movement above, Blancpain calibre 64-1. The only certified chronometer in all of the Blancpain collections, and their only regular production steel-cased watch fitted with a sapphire display back, it is omitted from mention in their literature with a modesty bordering upon shame. The 64-1 is based on one of the last of a long line of Peseux handwound calibres, the 7001. At 10 1/2 lignes and 2.5mm thick, it runs at a stately 21,600 vph beat rate. In making it suitable for their use, Blancpain completely reconstructs the top plate elements, and finishes every detail peerlessly. The attention lavished on this movement results in a price point reserved for first tier watches.  "Peseux" is in fact not not the name of a manufacture, but instead refers to the locale of Peseux within the Boudry district of the canton of Neuchatel, where small independent ebauche producer Charles Bernese began in 1923. It was assimilated by Ebauches S.A. ten years later in 1933, though it remained independently managed. The "Fabrique d'ebauches de Peseux, S.A." began producing the calibre 7001 in 1971, as it would until 1985 when the long history of Peseux-produced handwinds came to an end -- the year that Ebauches SA became the present consolidated ETA SA Fabriques d'Ebauches. Production of the movement was only recently restarted, though now at one of the ETA factories in Grenchen. "Peseux" is in fact not not the name of a manufacture, but instead refers to the locale of Peseux within the Boudry district of the canton of Neuchatel, where small independent ebauche producer Charles Bernese began in 1923. It was assimilated by Ebauches S.A. ten years later in 1933, though it remained independently managed. The "Fabrique d'ebauches de Peseux, S.A." began producing the calibre 7001 in 1971, as it would until 1985 when the long history of Peseux-produced handwinds came to an end -- the year that Ebauches SA became the present consolidated ETA SA Fabriques d'Ebauches. Production of the movement was only recently restarted, though now at one of the ETA factories in Grenchen.While many speak casually of generic movements being "modified" by watch companies - referring to little more than basic functional finishing and a few decorative Geneva Bars, this is a rare example of what real watchmaking skill can actually do to transform a basic ebauche into a first class movement. It is sad to see it relegated to obscurity, and I expect that it will eventually be replaced by a 10 1/2''' or 11 1/2''' handwind by F. Piguet.  Our first complication is often a feature taken for granted, but when executed correctly on a traditional savonnette calibre it adds a wonderful depth and grace to the movement -- indirect center seconds . I feel that the angularity of the basic calibre is softened and enhanced by the masterful addition of the center seconds bridge and the exposed indirect seconds wheel. On its own, the basic calibre 10 1/2''' No. 48 is unique and well-loved, with a following that is reminiscent of the Pythagorean cult of antiquity. Originally designed by Andre Frey in 1943, it was only later that the addition we see above finally resulted in calibre Minerva calibre 49. This particular iteration of the movement is one of a limited production of 49 pieces per annum. Like most movement designs of this vintage, it beats 18,000 times an hour. While these movements were traditionally given a flat matte and gilt finish, the "display-back revival" has seen their cal. 48 top plate finished with Geneva Bars and rhodium plate, and now the 49 has been given the luxury treatment throughout -- probably the most luxuriously finished movement ever produced by Minerva. It is a notable accomplishment for this small manufacture in Villeret.  Our second and final complication, a single-button chronograph, is integrated into a 3/4 plate calibre like the Lange L941 at top -- as are most of the handwound Lemania chronographs. Despite its apparent complexity, the depth of the integration means that there is almost no additional jeweling required beyond that normally used for the base movement. Part of the beauty of the image above is that it allows one to clearly see the 3/4 plate calibre beneath the chronograph works. This highly-crafted chronograph movement by Patek Philippe expatriate Roger Dubuis is based on the little seen Lemania calibre 2220. The movement runs at 18,000vph and I have seen it fitted with anywhere from 16 to 21 jewels -- like any ordinary handwind. Its unusually large 15 ligne size would seem to hint at an early origin as a pocket watch chronograph movement, though the earliest evidence I can find of its existence is in wristwatches of the 1940s when it was known as Lemania calibre CHT 15. I have always had a particular preference for single-button chronographs. They are obsolete even within the anachronistic context of mechanical chronographs, and they lack a real function offered by the two-button chronographs that have all but replaced them, but there is an elegance, a charm -- a simplicity that they have that eludes their younger siblings.  What the future holds for mechanical watches is at best uncertain. As an anachronism and a form of traditional art and craft, it poses both great expense at entry and for maintenance. Master watchmaker George Daniels has speculated that the rising costs of the latter will eventually make the "fruit salad" complications, which are so sought after today, prohibitive to own over the long term and eventually obsolete. I imagine that this would lead once more to a precarious existence for the mechanical watch, or to a return to the simplicity of the basic automatic "gentleman's watch" which was the standard just before the dawn of quartz. While movements like the ones we have seen above would certainly have a place within such a scenario, I feel that their economic advantages are really the very least that they have to offer. I hope that others can discover the true appeal and intimate connection offered by the simple handwound watch, and an understanding and appreciation of the classic beauty of the handwound movement. Image Credits: Music I by Gustav Klimt; scan by Mark Harden Lange calibre L941.1 by Danny IWC calibre 83 and Audemars Piguet calibre 3090 by Gisbert Joseph Patek Philippe calibre 23-300 by Mark Passey Blancpain 64-1 by Mike Margolis Peseux flag by Pascal Gross Minerva calibre 49 by David Gruber Roger Dubuis calibre 50 by Jing H. Goh Used with permission. All Rights Reserved |

Back to top of page |

Return to Time Zone

Home Page

Copyright © 2001-2004 A Bid Of Time, Inc., All Rights Reserved

E-mail: info@TimeZone.com