Hammer and Gong

by Carlos Perez

January 31, 2001

The oldest and most esoteric complications produced today come from the small family of repeaters and clockwatches. These wristwatches strike the time either en passant ("in passing") like traditional striking clocks, or on command like some pocket watches of the 18th and 19th centuries, and sometimes both like the fine carriage clocks from the golden age of complications. In a world with electricity and artificial lighting these acoustic complications lose much of their original purpose, but within the context of the post-quartz mechanical watch revival they become the ultimate expression of the craft of watchmaking.

Most confusing to today's wristwatch enthusiast is the extensive and specialized terminology that is used to describe these "striking" wristwatches and their functions. I have set out here to create a small reference that describes in simple terms the basic lingo of striking wristwatches and overviews a few of the benchmark calibres in production today. I will leave subjective impressions of comparative acoustic performance, as well as a comprehensive technical explanation of the complex mechanics involved to those better qualified.

In all cases I have attempted to list and employ terms as traditionally defined and used in common for striking clocks and watches. Also note that some manufacturers appear to stray from "proper" usage. Additional difficulties lie in the obsolescence of English terminology relative to French terminology and modern French usage. These archaic English terms, while less glamorous than the French alternatives, are still clearer to the English speaker and due to that lack of glamour may prove to be more useful.

Racks and snails

It is said that the origin of the long tradition of clockwatches - at least in simpler forms - is lost in the mists of antiquity, but were preceded by the development of striking clocks by a few centuries. The rack striking mechanism still in use by modern striking wristwatches was invented in 1676 by English clock and watchmaker Edward Barlow (1636 - 1716), replacing the less sophisticated count wheel system. In the 1680s the development of repeaters was begun by another English clock and watchmaker, Daniel Quare (1649 - 1724), who would eventually hold the patent for the invention.

It is said that the origin of the long tradition of clockwatches - at least in simpler forms - is lost in the mists of antiquity, but were preceded by the development of striking clocks by a few centuries. The rack striking mechanism still in use by modern striking wristwatches was invented in 1676 by English clock and watchmaker Edward Barlow (1636 - 1716), replacing the less sophisticated count wheel system. In the 1680s the development of repeaters was begun by another English clock and watchmaker, Daniel Quare (1649 - 1724), who would eventually hold the patent for the invention.Distantly related to the pitched family of idiophonic instruments, the bell-like sounds are produced by small hammers which strike wire gongs. These "gong springs" were invented by Abraham-Louis Breguet in 1783, replacing the small bells and "saucer-shaped" gongs of traditional striking clocks and early striking watches. Each note is produced by a single hammer and gong pairing that must be hand-tuned for pitch and volume -- which includes tweaking the striking force of the individual hammer. This is a laborious and time-consuming process which adds greatly to the cost of the finished product.

In the repeater form of the striking watch, the slide on the side of the case powers the strike mechanism by winding a spring as it is depressed. Controlling both the unwinding of the spring and the strike of the hammers is the centrifugal governor -- the "escapement" of the repeater mechanism, if you will. The hissing sound often remarked on is a by-product of the operation of the governor, much as ticking is of a lever escapement. The hiss is of course considered undesirable due to the acoustic nature of the complication, and moderation of the hiss is met with various levels of success by the different manufactures, and is something which Patek Philippe is particularly esteemed for.

A carillon (lit. "chime") is any striking complication (clockwatches and repeaters) with three or more hammer and gong sets, rather than two sets -- which is standard. So instead of just bass and treble notes they have a bass note, a middle note, and a treble note, etc. This permits the use of different notes for quarter hours, and even the reproduction of musical chime sequences in watches like Girard-Perregaux's Opera One and Gerald Genta's Grand Sonnerie -- both of which have four hammer and gong sets. One will typically find that all striking watches are described as "chiming," but this is only properly used in reference to carillons.

Possibly overlooked factors in the acoustic performance of many striking watches is case volume, as well as the issue of metal vs. display backs. Some of these factors have been taken into account in the design of IWC's Il Destriero Scafusia. In this case the crystal itself becomes a part of the idiophone as the sound is transmitted to it via a "bridge" and it is allowed to vibrate freely -- a sapphire soundboard.

Repeaters

Of the striking complications it is the repeater which is most common, and made so by the availability of minute repeater ebauches from Nouvelle Lemania, Frederic Piguet, Christophe Claret, and others. While most are implemented as traditional integrated hand-wound calibres, a few like F. Piguet calibre 33 can be modified to accept automatic winding, or are repeater modules attached to an automatic base movement -- as with the Kelek repeaters.

The standard strike pattern for repeaters (and clockwatches) uses a base note for hours, alternating or combined bass and treble notes for quarters, and treble notes for minutes. As previously mentioned, chiming repeaters permit the use of a separate note for quarters, and there is often some variation in specific implementation from manufacture to manufacture, and from movement to movement.

Minute Repeater -- on command it strikes the hours, quarter hours, and minutes.

Five-Minute Repeater -- on command it strikes the hours, quarter hours, and five minute segments, or the hours and one note per five minute segment.

Half-Quarter Repeater -- on command it strikes the hours, quarter hours, and half-quarter hours (segments of 7 to 14 minutes).

Quarter Repeater -- on command it strikes the hours and quarter hours only.

Clockwatches

In French known as sonnerie (lit. "ringing.") watches, clockwatches are far more rare than repeaters and appear to be exclusively of "in-house" manufacture at this time. I do not know why they are so rare relative to the repeater market, but it has been suggested that dual train grande sonneries merit "grande complication" status in their own right.

In French known as sonnerie (lit. "ringing.") watches, clockwatches are far more rare than repeaters and appear to be exclusively of "in-house" manufacture at this time. I do not know why they are so rare relative to the repeater market, but it has been suggested that dual train grande sonneries merit "grande complication" status in their own right.While their repeater relatives are powered by a repeater slide and spring mechanism, the autonomous operation of a passing strike train requires the continuous power supply of its own mainspring. Older clockwatches that struck both the hours and quarters had to have a separate strike trains for each (hour strike train & quarter-hour strike train), resulting in "triple train" clockwatches with three mainsprings. Modern designs appear to be more efficient, and can accommodate both within a single strike train.

Using a sonnerie simply entails choosing a strike mode via a slide bolt on the case -- the watch itself does the rest. All clockwatches are of course equipped with a Strike-Silent, or Silence mode. In a clockwatch with repeater, the repetition function is also powered by the second mainspring, and is usually operated by a button rather than by a slide. The drawback here is that repeated operation of the repeater will quickly deplete the strike train's power reserve.

Full Strike (grande sonnerie) -- strikes the hours on the hour, and strikes the hours and the quarters on the quarter hours, both en passant.

Quarter Strike (petite sonnerie) -- strikes the hours on the hour, and the quarters only on the quarter hours, both en passant.

Hour Strike -- strikes the hours only on the hour, en passant.

Passing Strike (sonnerie en passant) -- strikes once only on the hour, en passant.

Full Strike Minute Repeater -- en passant it strikes the hours on the hour and strikes the hours and the quarters on the quarter hours. On command it strikes the hours, quarter hours, and minutes.

Full Strike Quarter Repeater -- en passant it strikes the hours on the hour and strikes the hours and the quarters on the quarter hours. On command it strikes the hours and quarter hours.

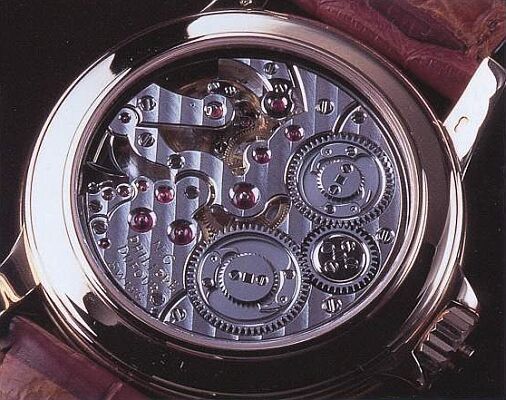

The most coveted movement produced by the most esteemed manufacture in Switzerland, Patek Philippe Repetition calibre 27 exists in two basic variations: R 27 PS as shown above, an automatic with inset micro-rotor, and as RTO 27 PS, the hand-wound repeater with tourbillon. Much of the beauty of these fraternal twins lies in the absence of conventional modularity employed in producing the two different movements. Modularity can be very efficient -- as seen in many of the movements of Frederic Piguet -- but the finished movement always bears the physical scars of its modularity.

The automatic R 27 PS is the elder sibling, having been introduced in 1989 for the celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the original Patek, Czapek, & Co. The extensive redesign as a hand-wind with tourbillon regulator (which uses much of the space originally taken by the micro-rotor) finally saw the introduction of the RTO 27 PS in 1995 (the 150th anniversary of Patek & Co.), with 11 less jewels and an additional 1.5mm in height. Both movements are used in stand-alone form, and for several perpetual calendars: R 27 Q, R 27 PS QR, and RTO 27 PS QR.

In technical terms, Patek Philippe calibre R 27 PS is a very modern reinterpretation of the classical repetition minutes complication -- particularly when contrasted with the repeaters of Lemania (to be shown) and Claret (pictured previously as used by RGM). 28mm in diameter and 5.05mm in thickness, it has 39 jewels, and a 48 hour power reserve at a 21,600 v/h beat rate. Now on the 150th anniversary of Patek Philippe & Co., it remains the one and only minute repeater with micro-rotor automatic winding.

From Audemars Piguet's "Jules Audemars" collection comes the Grande et Petite Sonnerie Repetition Minutes Carillon, Reserve de Sonnerie et Dynamographe -- otherwise known as the watch with the longest name in the world. In less frivolous terms it is one of the most complex striking wristwatches ever produced, with three gong chime.

The use of the term "petite sonnerie" here is atypical when compared both to historical examples (clocks and pocket clockwatches) and its present peers amongst wristwatches (Dufour and Journe), as in petite sonnerie mode it chimes only the hours and not the quarters. I am unclear on the conventions in this matter, and whether this "hour strike" is an alternative to "quarter strike" in the French usage of "petite sonnerie."

The use of the term "petite sonnerie" here is atypical when compared both to historical examples (clocks and pocket clockwatches) and its present peers amongst wristwatches (Dufour and Journe), as in petite sonnerie mode it chimes only the hours and not the quarters. I am unclear on the conventions in this matter, and whether this "hour strike" is an alternative to "quarter strike" in the French usage of "petite sonnerie."The Dynamographe is a new development of the Jules Audemars Grande et Petite Sonnerie Repetition Minutes Carillon (the watch with the second longest name in the world) and its calibre 2890 -- originally introduced in 1997. The dynamograph itself, labeled on the watch as the "couple" indicator, uses a direct-force sensor to monitor the torque output from the mainspring barrel, and shows when the movement is operating at the optimum torque level for best isochronism. The watch also features a power reserve indicator for the strike train, the "reserve de sonnerie."

Calibre 2891 in the Dynamographe is 29.9mm in diameter and 5.8mm in height, has 57 jewels, and a 48 hour power-reserve at a 21,600 v/h rate. The separate strike barrel has a 60 hour power reserve in petite sonnerie mode, or 20 hours when in grande sonnerie mode. As the two barrels are independent of each other, one winds the strike barrel by turning the crown clockwise, and the mainspring barrel by turning the crown counter-clockwise. With its other masterpiece, the very classical Repetition Minutes Carillon calibre 2866, Audemars Piguet bears the distinction of being the only manufacture of both chiming repeaters and chiming clockwatches (with repeat) for the wrist.

Shown above is the most widespread minute repeater ebauche used in haute horlogerie today -- Nouvelle Lemania calibre 399. It is used by ancient names like Vacheron Constantin and Breguet, boutique makers like Daniel Roth, and as a base for the automata and some of the jaquemarts of Ulysse Nardin (shown at bottom). I suspect that like Lemania's tourbillon (calibre 387) and hand-wound column wheel chronographs (calibres 2320 and 2220), that this is a vintage design of great antiquity. It bears many signs of such an origin -- the black-polished cap-jewel plate, the 18,000 v/h beat rate, the swan neck regulator, and the overcoil hairspring.

It can probably be considered a standard by which other minute repeaters should be judged, whether traditional or novel in form, as it is a living representative of the past and not a re-creation. Its straight "revolver" top plate pattern is not often seen today, as its modern competitors all favor a "curved bar" format -- including Frederic Piguet calibre 33 and Audemars Piguet calibre 2866. For those few watch manufacturers judged as worthy by Lemania, this movement remains their only means of ever producing a coveted repetition minutes wristwatch.

As a magnificent first personally branded work of a newly independent watchmaker, Philippe Dufour's Grande et Petite Sonnerie Repetition Minutes became the first wristwatch of its type when he introduced it at Basel in 1992. That first edition of the watch was very French-classical in design with a white enameled dial, Breguet hands, roman numerals, and a case with a hinged dust cover to conceal the display back. The case also featured the fairly obtrusive slide-bolts that are necessary to operate the strike mechanism and its various modes.

It wasn't until 1999 that he introduced the refined model shown above. On this he has hidden the slide-bolts beneath a hinged bezel, and revealed the strike train with a sapphire dial (image #4 from top). The elegant repeater co-axial button continues to project subtly from the crown -- which is also a unique feature of this striking watch (pun intended). Another point of note is that has a "proper" petite sonnerie, with quarter striking as defined above --- a feature shared by the Souveraine Sonnerie of F.P. Journe.

At least superficially, its movement appears to have been inspired by an antique Patek Philippe pocket watch which he restored, and at 32.5mm in diameter and 7mm in height it straddles the line between a pocket watch calibre and a wristwatch calibre in size. It bears 35 jewels, a freesprung adjustable-mass balance and overcoil hairspring, and has a power reserve of 38 hours at a 21,600 v/h rate. The strike barrel has a 24 hour power reserve, and both mainsprings have Maltese Cross stopworks. Like the Audemars Piguet Dynamographe, winding is bi-directional.

For most of us the striking watch is, and will remain, an unattainable dream. The world of repeaters and clockwatches is one that we can only contemplate in abstraction as an ideal of high craftsmanship, and as a link to the senses and sensibilities of an age long past. Beyond the enigma of tourbillons and the pandemonium of grand complications, the striking watch in its pure form is the zenith of what we hold dear in watchmaking -- and all that we aspire to.

Image Credits

San Marco Sonnerie en Passant and Forgerons Repetition Minutes by Ulysse Nardin

Christophe Claret Repetition Minutes by Roland G. Murphy

Patek Philippe calibre R 27 PS and Breguet calibre 567 by Jing H. Goh

Audemars Piguet Dynamographe from a private collection.

Grande et Petite Sonnerie Repetition Minutes by Philippe Dufour

All Rights Reserved