| |

While a wristwatch is much more than just a miniature pocket watch strapped to the wrist, the heritage of today's classiques in undeniably linked to the classical watchmaking and designs of the 18th and 19th centuries -- the twilight of the Ancien Regime. The revival of Greco-Roman elements and principals which we deem "Classical" permeates the western arts of the last several hundred years, but its purist and often austere aesthetic would not find full expression in the new and increasingly popular personal timekeeping objet d'art until the close of the Baroque age.

With the death of Louis XIV, his five-year old great-grandson Louis XV (1710 to 1774) ascended to the throne of France. This change of the guard also brought great change to the arts and crafts of the great nation. With a Regency in temporary control, the tastes of the nobility turned against the heavy baroque magnificence of the Sun King's reign and his Court at the Chateau de Versailles ("palais" only to the vulgar). Their return to Paris from the world's grandest hunting lodge fomented a new style in decor and adornment, la belle simplicite of the Rococo. With the death of Louis XIV, his five-year old great-grandson Louis XV (1710 to 1774) ascended to the throne of France. This change of the guard also brought great change to the arts and crafts of the great nation. With a Regency in temporary control, the tastes of the nobility turned against the heavy baroque magnificence of the Sun King's reign and his Court at the Chateau de Versailles ("palais" only to the vulgar). Their return to Paris from the world's grandest hunting lodge fomented a new style in decor and adornment, la belle simplicite of the Rococo.

While this Parisian style originated well before Louis XV truly came into power, his preference for it prolonged its lifespan long beyond what it would have otherwise been. Now generally thought of as the Louis XV style, it was "lighter and more intimate" than the "grand manner" of Louis XIV, pursuing grace rather than magnificence. The broad and rich use of colour typical of the Baroque was supplanted by the simple use of white and gold. Scrollwork, floral and other light patterns replaced engraved figures, stories, and themes. The term Rococo comes from the word rocaille, which refers to the sensuous swirling shell and pebbled patterns which were used so extensively.

This intermezzo between two periods of grand art and architecture was marked by increasing interest in the use of highly crafted luxury items. Artisans, rather than artists, ruled the day as decorative arts and "craft" supplanted "Art." The great works of the Baroque period were closeted away as small "Cabinotier" workshops spread throughout Paris producing luxury goods. These objects became smaller and thinner -- more delicate in feel.

The Oignon watch which was in fashion at the turn of the century was the last form of the watch under the rule of Louis XIV. Fat and bulbous and ornately decorated, it reflected clearly both its name and its period. With the shift in mood and sentiment, the beginnings of what would become the classical watch took root. (Of course, even though the Rococo fashion came to predominate, more opulent Baroque forms continued to exist and be produced, particularly as a product of Swiss Cabinotiers.)

The first distinguishing and classical element the Rococo period is the plain white enamel dial with bold roman or arabic numerals -- often used in combination with arabics to denote minutes. Imagery that once dominated the entire watch was now moved to the back cover with painted enamel or engraved scenes, bordered with engraved rocaille or arabesques. The narcissism of Louis XV's court, Society, and the growing bourgeois class, delighted in portraiture -- particularly portraits and images of women which became the popular theme for case back decoration. The elaborate decoration concealed thus eventually included automata, especially erotic automata which gained popularity in the late Rococo (and which remains with us today).

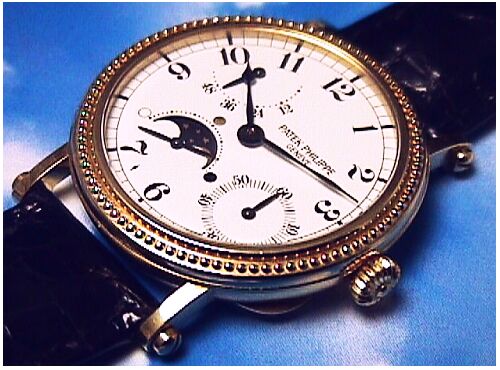

Rocaille "pebbling" on bezels, as with the Patek Philippe 5015 (above) became especially popular in the late Rococo, but in our age remains unique to a few models from Patek Philippe. The painted enamel caseback is likewise rare, and the allegorical decoration of Jaeger-LeCoultre's "Four Seasons" Reversos evoke the beauty of this largely discarded usage.

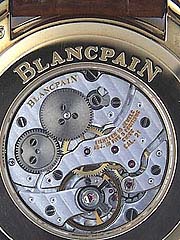

The second classical element which took root in the Rococo is the geometric purism of the round case, which is one of the founding philosophies of the modern Blancpain. The last gift of the Rococo to the emergence of the classical watch was the "less is more" value of thinness. The pursuit of thinner watches was led by Swiss-born Parisian watchmaker Jean-Antoine Lepine (1720 - 1814). The second classical element which took root in the Rococo is the geometric purism of the round case, which is one of the founding philosophies of the modern Blancpain. The last gift of the Rococo to the emergence of the classical watch was the "less is more" value of thinness. The pursuit of thinner watches was led by Swiss-born Parisian watchmaker Jean-Antoine Lepine (1720 - 1814).

In 1760 Lepine invented the bridged calibre, which made the movement mechanically simpler, thinner, and easier to service. The bridged "Lepine calibre" would eventually become the standard of French and Swiss watchmaking while the rest of the of the world continued to use the full-plate calibre (eventually adopting the 3/4 plate design). He also invented the floating mainspring barrel which led to the creation of ultrathin watches, and which are still used by the ultrathin movements of our day (like the F. Piguet 21 at right). I suspect that he is also responsible for the simple matte gilt finish that was standard for these movements, and which eventually became the standard of French and Swiss movement finishing until the Genevois style came into vogue.

Lepine himself, and another Swiss-born Parisian watchmaker to come, were indicative of a certain shift in the world of French watchmaking. The repeated infusion of French watchmakers (fleeing religious persecution) into Geneva and environs in the 16th and 17th centuries, had led not only to the founding and growth of Swiss watchmaking, but to close ties between Cabinotiers in France and the supply of parts and ebauches from a growing number of ateliers in Geneva, the valle de Joux, and Neuchatel. As time progressed there was a growing prevalence of French designs utilitizing Swiss mechanics, and a growing popularity of Swiss-French watches produced by Cabinotiers in Geneva -- for instance the beginning of the Vacheron watchmaking dynasty in 1755.

The declining years of Louis XV's reign saw the beginning of a "Classical" reaction against the dainty opulence of the Rococo. With his death in 1774, his grandson Louis XVI (1754 to 1793) came into power. Unlike his forebears Louis XVI had little interest in the arts, and the absence of royal perogative resulted in the grande simplicite of a new Classical movement. In some ways French Neoclassicism became even more stern than Cato's ideal vision of Rome -- though more refined and less "heavy" than the Palladian movement in England.

This "Neoclassical" movement in architecture and decor allowed the French watch to slowly shed its Rococo facade as it evolved into its first purely classical form. This transition in French watchmaking was led by Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747 to 1823). The Swiss-born and French-trained watchmaker opened his own shop in Paris in 1775, one year after the death of Louis XV.

Though at first his watches were indistinguishable from those of his contemporaries, this changed with his first great design innovations in 1783 -- his signature refinement of arabic numerals and the creation of "pomme" watch hands; both of which continue to bear his name. Shown here on the recently introduced 5022 Officer's watch by Patek Philippe, it is the first truly unique product of the classical watchmaking period in France, and one of the oldest designs still in use today -- though it is unfortunately somewhat rare.

His next great design innovation came just three years later in 1786 with the introduction of the guilloche dial. While the rose engine lathe had been long used for creating decorative patterns and engraving on everything from woodwork to watches, his innovation of the simple repetitive guillochage patterns which he applied to watch dials would revolutionize French watch design. These patterns brought not only a high-craft aesthetic to the finished watch, but served the practical purpose of attenuating reflection which made the watch easier to read.

Of course there is more to Breguet as a watchmaker than "mere" design work. Though he was known to use ebauches which he sourced from the Vallee de Joux and Le Locle, in 1791 he finally designed and produced his own "Breguet calibre," based on the work of Lepine. Taking advantage of these thinner movement designs, he introduced the thin and flat case devoid of embellishment or decoration. He also began a highly complicated watch for Queen Marie-Antoinette, but that great work would be interrupted by the increasingly violent French Revolution, when in 1793 he fled back to Switzerland.

In 1795 he returned to Paris, rebuilt his ruined shop, and began working in an almost creative frenzy, producing in a single year the first tourbillon movement (not patented until 1801), the perpetual calendar, and the overcoil balance spring. This was followed by continual innovation and invention which seems undisturbed by the constant political and social turmoil of France in those years of Revolution, Republic, and Empire -- a period which saw Geneva, the valle de Joux, and Neuchatel annexed by France.

The heavy and dark "Empire Style" favoured by Napoleon Bonaparte only reinforced the French Neoclassical movement, as he too attempted to adopt the legitimacy of the Roman Imperators. Though it had great influence on achitecture and decor, his rule was too brief to have any influence upon watch design -- other than for the apocryphal story wherein he invented the "half-hunter" watch through judicious application of his sword.

With the defeat of Bonaparte in 1813, western Switzerland was liberated from French rule, and in 1815 Geneva and Neuchatel finally joined the Swiss Federation. In France, the anciene regime of the Bourbon kings was restored with the ascension of Louis XVIII (1755 - 1824) to the throne. A.L. Breguet, watchmaker to Kings, Queens, and Emperors, continued to build his legacy in the watchmaking craft, and by the time of his death, the "Breguet Look" had nearly become the French national style.

By the end of the short rule of Louis XVIII's successor Charles X in 1830, the use of guillochage patterns had spread to case and bezel decoration, replacing the enamel-work, pictorial engraving and rocaille that had been the standard for a century. The Patek Philippe 3796 (above) with Clos de Paris guilloche bezel, is one of the last traces of this point in classical watch design, along with a handful of other models produced by this manufacture, Audemars Piguet, and Parisian jeweler Boucheron.

Less common than white enamel or silvered guilloche dials, was the matte-finished gold dial. Devoid of the extensive engraving of the Baroque period and marked simply with roman numerals, it became almost understated. While it never attained its former status, its limited use by Breguet and his contemporaries reconciled it with the classical spirit.The unsilvered gold guilloche dial was another, though even less common usage. Less common than white enamel or silvered guilloche dials, was the matte-finished gold dial. Devoid of the extensive engraving of the Baroque period and marked simply with roman numerals, it became almost understated. While it never attained its former status, its limited use by Breguet and his contemporaries reconciled it with the classical spirit.The unsilvered gold guilloche dial was another, though even less common usage.

The classical French watch would take its final and most evolved form by the end of the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe I in 1848 -- the last King of France. Decoration of the thin, round cases became simpler and simpler, eventually to be polished smooth. Elements like Breguet hands, and the white enamel or silvered guilloche dial, Roman or Breguet numerals, had become the accepted standards -- as had the Lepine-style bridged movement.

But in reaching their peak they also reached the beginning of their decline. By that time the French were moving further and further away from the actual craft of watchmaking as they succumbed to the Swiss system of etablissage. There remained a lineage of a few influential French watchmakers like Edmond Jaeger -- a Parisian chronometer maker who would eventually partner with Jacques-David LeCoultre of Le Sentier in 1903. But they have dwindled away, and all that remains in France now is the watches of old jewelry houses like Chaumet (est. 1780), Cartier (est. 1847), and Boucheron (est. 1858).

While the true watchmaking heritage of France is long dead and mostly forgotten, its legacy lives on in the watchmaking of Switzerland: Its offspring, rival, and ultimate successor -- where French remains the language of watchmaking. The old Genevan houses of Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe are our

direct bridge to the pinnacle and terminus of classical French watchmaking, and the reborn brands of Blancpain and Breguet attempt to the evoke its purism in modern reinterpretations. The old regimes may have fallen, but the classical watch lives on.

Image credits:

Ultraslim Demi-Savonnette by Blancpain, S.A.; scan by Mike Margolis

Louis XV by Louis-Michel van Loo (1707 - 1771)

Patek Philippe 5015 by Edwin Leung

Blancpain calibre 21 by Gisbert Joseph

Patek Philippe 5022 Officer's and Breguet 3580 by Jing H. Goh

Patek Philippe 3796 by Dale Gordineer

Vacheron Constantin Les Historiques by Thomas Mao

Imaginary view of the Great Gallery of the Louvre in Ruins by Hubert Robert (1738 - 1808)

Copyright © Carlos A. Perez 2000

All Rights Reserved

|

|

|