"The Best Years of Our Lives" by John Davis and Terry Russell March 10, 2001

Images with colored borders may be clicked to access larger images

In the lexicon of watch connoisseurs, acronyms and numerical codes can express much. From makers like PP, AP, JLC, IWC and even ETA we can discuss much about the 215, the 3100, the 889, the 5000 or even the 7750 or 2892. Some of these numbers represent a movement of such renown that the number will be present in the description of the watch on a dealer's website even before the decade of manufacture or the case material. One of these most revered of numbers is the simple and beautiful Cal. 89 from IWC.

The Cal. 89 is a simple, robust, time only movement that has an air of elegance in its design and execution that separates it from the more pedestrian movements of its time. It does not have the lavish finishing of the finest watch movements but one would not expect it to. It is at its heart a working man's watch of the highest quality. It is a 12 ligne, manual wind movement consisting of some 79 parts including 19 screws and 16 jewels and features a full bridge layout with an indirect center seconds hand and manual winding. Its escapement uses a semi-equidistant pallet and simple regulator acting on a hairspring with a Breguet overcoil. For the purposes of researching this article I examined three Cal. 89 movements in the course of servicing and/or repairing them. The movements examined were a model from 1950 with a yellow gold case and black dial belonging to Terry Russell, a model from 1956 with a stainless steel case and white dial belonging to Kent Lee, and a model from 1962 with a rose gold case and white dial also belonging to Terry Russell.

The Cal. 89 is a simple, robust, time only movement that has an air of elegance in its design and execution that separates it from the more pedestrian movements of its time. It does not have the lavish finishing of the finest watch movements but one would not expect it to. It is at its heart a working man's watch of the highest quality. It is a 12 ligne, manual wind movement consisting of some 79 parts including 19 screws and 16 jewels and features a full bridge layout with an indirect center seconds hand and manual winding. Its escapement uses a semi-equidistant pallet and simple regulator acting on a hairspring with a Breguet overcoil. For the purposes of researching this article I examined three Cal. 89 movements in the course of servicing and/or repairing them. The movements examined were a model from 1950 with a yellow gold case and black dial belonging to Terry Russell, a model from 1956 with a stainless steel case and white dial belonging to Kent Lee, and a model from 1962 with a rose gold case and white dial also belonging to Terry Russell. The Clothes

From the outside, all three watches have an elegance and simplicity often found in watches of this period. I did find some truth to the reports that their outer trappings are not quite as high quality as the movements within. I can't comment on the quality of the printing on the dials, as I can't be sure any of them are original, but I found the raised markers (as opposed to applied) to be a little out of place. The gold hands are attractive but are plated as opposed to solid, which I found curious in light of having solid gold cases. Each of these watches features a very well executed, snap back case, which still clicks smartly into place after close to half a century of periodic check-ups. The size and proportion of these watches (36 mm across) make them perfectly suited for dress or casual wear today although a certain amount of care should be exercised as they have no water proofing around the stem and crown.

From the outside, all three watches have an elegance and simplicity often found in watches of this period. I did find some truth to the reports that their outer trappings are not quite as high quality as the movements within. I can't comment on the quality of the printing on the dials, as I can't be sure any of them are original, but I found the raised markers (as opposed to applied) to be a little out of place. The gold hands are attractive but are plated as opposed to solid, which I found curious in light of having solid gold cases. Each of these watches features a very well executed, snap back case, which still clicks smartly into place after close to half a century of periodic check-ups. The size and proportion of these watches (36 mm across) make them perfectly suited for dress or casual wear today although a certain amount of care should be exercised as they have no water proofing around the stem and crown.The Keyless Works

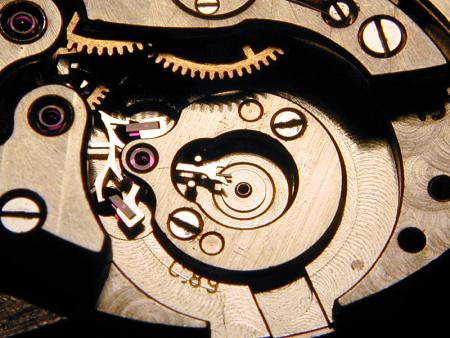

To take the winding of the watch as the starting place for examining the movement, let us begin with the keyless works. The keyless cover, clutch lever and detent lever are sometimes referred to as the fingerprint of a movement. Even in watches with otherwise very similar layouts, these three pieces are typically distinct and recognizable and can be used to determine the base ebauche used when it cannot otherwise be ascertained. You'll notice in this picture (taken before cleaning the movement) the amount of dirt, corrosion and grease that has built up over the years due to the unsealed winding stem. The keyless cover's finish is straight grained on the top and polished underneath where it interacts with the clutch lever and it is secured with two screws. The clutch lever holds the clutch firmly against the Breguet teeth of the winding pinion under the action of a simple wire spring. In a higher quality movement a formed spring would have been used as is required by the Geneva Seal.

To take the winding of the watch as the starting place for examining the movement, let us begin with the keyless works. The keyless cover, clutch lever and detent lever are sometimes referred to as the fingerprint of a movement. Even in watches with otherwise very similar layouts, these three pieces are typically distinct and recognizable and can be used to determine the base ebauche used when it cannot otherwise be ascertained. You'll notice in this picture (taken before cleaning the movement) the amount of dirt, corrosion and grease that has built up over the years due to the unsealed winding stem. The keyless cover's finish is straight grained on the top and polished underneath where it interacts with the clutch lever and it is secured with two screws. The clutch lever holds the clutch firmly against the Breguet teeth of the winding pinion under the action of a simple wire spring. In a higher quality movement a formed spring would have been used as is required by the Geneva Seal.In the 1950 model that I examined, significant rust had built up on the ratchet teeth of the winding pinion and it had to be replaced. Apparently someone had already replaced the clutch itself, as its corresponding teeth were pristine. Luckily the proliferation of Cal. 89s and the extended years of production make parts availability generally a non-issue.

One interesting feature of the Cal. 89 is the presence of two intermediate wheels for handsetting. At first this seemed to me like a concession to the size or layout of the movement. I later realized that this reversal makes the hands move in a direction that relates more intuitively to the direction the crown is turned (turning the crown towards you moves the hands clockwise). I'm still not certain that was the intention of the two intermediate wheels but it is an interesting byproduct at least. Some JLC movements (and doubtless some by other manufacturers) have this feature as well.

The Barrel and Click Wheel

The click in the Cal. 89 consists of only one formed part and a wire spring and provides the same function as the more common rotating/screwed-in clicks without the possibility of sticking. It is not as crude or cheaply executed as the single piece click/spring found in the Valjoux 7750 or the Seiko 7S26 but functions on the same principles. I find clicks of this nature to be sturdier and less prone to wear than rotating clicks and variations on this click style can be found in the watches of Philippe Dufour and the new Jules Audemars line by Audemars Piguet. The barrel in the Cal. 89 has four holes in it. It has two holes in the barrel cover, one in the top of the barrel and one hole in the side. The holes in the top of the barrel and the cover are to hold the T-ends of the mainspring in place and the other hole in the cover is in all likelihood to facilitate removing it (with a screwdriver) but the purpose of the fourth hole (in the side of the barrel) is a mystery to me.

The click in the Cal. 89 consists of only one formed part and a wire spring and provides the same function as the more common rotating/screwed-in clicks without the possibility of sticking. It is not as crude or cheaply executed as the single piece click/spring found in the Valjoux 7750 or the Seiko 7S26 but functions on the same principles. I find clicks of this nature to be sturdier and less prone to wear than rotating clicks and variations on this click style can be found in the watches of Philippe Dufour and the new Jules Audemars line by Audemars Piguet. The barrel in the Cal. 89 has four holes in it. It has two holes in the barrel cover, one in the top of the barrel and one hole in the side. The holes in the top of the barrel and the cover are to hold the T-ends of the mainspring in place and the other hole in the cover is in all likelihood to facilitate removing it (with a screwdriver) but the purpose of the fourth hole (in the side of the barrel) is a mystery to me.

The Power Train

With an examination of the second wheel, the unique approach to indirect center seconds found in the Cal. 89 becomes apparent. The center wheel is dished in the center to the effect that the gear teeth are considerably higher than where the spokes attach to the wheel. The underside of the bridge that supports the center wheel, third wheel and indirect seconds pinion has a matching bulge with an opening in one side for the third wheel to interact directly with the indirect seconds pinion. This is a simpler arrangement than the typical indirect seconds arrangement whereby an auxiliary third wheel on top of the bridge drives the center seconds pinion (see the Mido 1200 C movement below, far right). The Cal. 89 approach is no doubt more expensive to manufacture because of the specially formed center wheel and the additional milling of the bridge but in addition to involving less parts (no auxiliary third wheel), it also allows the tension spring for the center seconds pinion to be fully recessed into the bridge. In this way the height of the movement is kept to a minimum while the delicate spring is protected from ham-handed repairers. A tension spring is a necessary evil associated with all indirect center seconds movements to keep the motion of the second hand as smooth as possible. IWC also chose to jewel the center seconds pinion while leaving the center wheel unjeweled on both sides (as was common in movements of that time period and some movements today).

With an examination of the second wheel, the unique approach to indirect center seconds found in the Cal. 89 becomes apparent. The center wheel is dished in the center to the effect that the gear teeth are considerably higher than where the spokes attach to the wheel. The underside of the bridge that supports the center wheel, third wheel and indirect seconds pinion has a matching bulge with an opening in one side for the third wheel to interact directly with the indirect seconds pinion. This is a simpler arrangement than the typical indirect seconds arrangement whereby an auxiliary third wheel on top of the bridge drives the center seconds pinion (see the Mido 1200 C movement below, far right). The Cal. 89 approach is no doubt more expensive to manufacture because of the specially formed center wheel and the additional milling of the bridge but in addition to involving less parts (no auxiliary third wheel), it also allows the tension spring for the center seconds pinion to be fully recessed into the bridge. In this way the height of the movement is kept to a minimum while the delicate spring is protected from ham-handed repairers. A tension spring is a necessary evil associated with all indirect center seconds movements to keep the motion of the second hand as smooth as possible. IWC also chose to jewel the center seconds pinion while leaving the center wheel unjeweled on both sides (as was common in movements of that time period and some movements today).

The tension spring is a hair-thin piece of beryllium bronze pinned into a rotating stud so that the tension can be adjusted with a simple twist of a screwdriver while the movement is running. In this way, the smoothness of the second hand can be observed as well as any detrimental effects on amplitude the extra drag might cause. A more common approach can be seen in the Mido movement, whereby a copper spring serves to create the necessary drag as well as acting as the pivot surface. To adjust the tension in such a design, the spring itself must be removed and bent, making precise adjustments impossible. It is critical that the spring be made of a metal that contrasts with steel for a couple of reasons. Not only would a steel on steel interaction (the pinion is made of steel) cause magnetism issues to arise over time, but the wear involved between metals with the same sized molecular structure is much greater regardless of how well polished the surfaces are. This is the reason that bushings are made of bronze (against steel pinions) and wheels are made of brass or gold (against steel pinion leaves). Beryllium bronze is a highly toxic substance and would not be used in a modern watch but offers a high degree of stiffness with the necessary amount of elasticity.

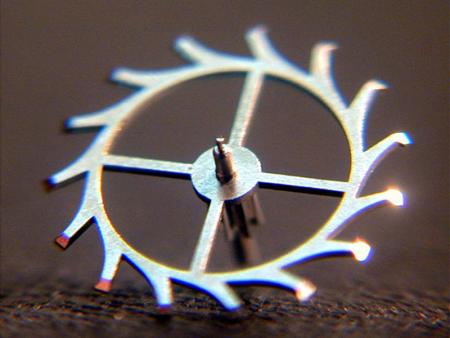

The jewels of the third, fourth and escape wheels are secured by pressed in gold chatons. One subtle feature that bespeaks the elegance of the overall design is the fact that every bridge screw (with the exception of the pallet bridge) is the same exact size. This is often not the case, thus causing watchmakers to replace the screws in the main plate when washing the movement. In this way guesswork, photographic memory and trial and error can be avoided during reassembly. In addition, each of these screws is beveled on the edges and slots. The wheels of the power train are all circular grained with beveled spokes (top side only) and beautifully formed epicycloidal teeth. The escape wheel has fifteen teeth and the acting surfaces are mirror polished even after potentially one billion impulses delivered each.

The Escapement

The pallets are secured in place by a beautiful, circular bridge held in place with two (relatively) large screws. The pallets themselves are nicely polished on the top while the underside is left unfinished as is common in all but the finest quality watches and the excess shellac under the pallet jewels has not been removed (as is also common). The balance is made of Glucydur and has screws for poising and adjustment. The hairspring, although reportedly made of Nivarox-Metelinvar, appears to be blued steel but I defer to IWC's information of course. The shape of the overcoil hairspring conforms to the rules laid out by Edouard Phillips for mathematically correct terminal curves and is attached to the collet in a position that minimizes the rate error for the crown down position. The curb pins offer a very snug fit which minimizes their influence on positional variation and the hairspring stud is affixed to the balance bridge via a small kidney shaped plate and two screws. This allows some flexibility in how close the stud lies to the balance staff and offers endless possibilities for timing adjustment without even touching the hairspring. In practice I found using the stud holder to effect positional variation to be a hit or miss proposition. Significant changes could be detected simply relative to which of the two screws was tightened first.

The pallets are secured in place by a beautiful, circular bridge held in place with two (relatively) large screws. The pallets themselves are nicely polished on the top while the underside is left unfinished as is common in all but the finest quality watches and the excess shellac under the pallet jewels has not been removed (as is also common). The balance is made of Glucydur and has screws for poising and adjustment. The hairspring, although reportedly made of Nivarox-Metelinvar, appears to be blued steel but I defer to IWC's information of course. The shape of the overcoil hairspring conforms to the rules laid out by Edouard Phillips for mathematically correct terminal curves and is attached to the collet in a position that minimizes the rate error for the crown down position. The curb pins offer a very snug fit which minimizes their influence on positional variation and the hairspring stud is affixed to the balance bridge via a small kidney shaped plate and two screws. This allows some flexibility in how close the stud lies to the balance staff and offers endless possibilities for timing adjustment without even touching the hairspring. In practice I found using the stud holder to effect positional variation to be a hit or miss proposition. Significant changes could be detected simply relative to which of the two screws was tightened first.

After a little trial and error though I found I was able to get respectable positional performance out of each of the examples without tweaking the hairspring at all (something that is almost always necessary otherwise). All three examples I saw featured Incabloc shock protection on the balance wheel pivots although reportedly not all Cal. 89s are so equipped. The two earlier examples had a screwed Incabloc housing on the bottom plate while the later example had the more common press fit variety. In each of the examples the cap jewel on the top side was considerably thicker than the lower cap jewel, a trend I've observed in a variety of watches although the reason for this is not clear to me. Possibly the theory is that a more significant shock could be realized from the direction of the dial side of the watch as the other side is protected by the wearer's wrist. Overall I found the escapement on the Cal. 89 to be user friendly and well executed. Apparently IWC agrees as they chose to use the same escapement (with a few minor changes) in their new Cal. 5000 movement.

The Motion Works

The dial train is unremarkable except for the attention to detail that the shape of the cannon pinion and hour wheel exhibit. Both the cannon pinion and hour wheel have a shoulder for their associated hands to ensure their proper height and the cannon pinion has a precisely squared groove running most of its length to minimize the frictional interaction between it and the hour wheel. I found this to be a nice touch that is not present in most other watches I've seen. The bottom plate has a nicely applied perlage (excepting the milled surfaces) and has many alignment holes that are a tell-tale sign of mass-production.

Conclusion

The IWC Caliber 89 is a simple, robust and well designed movement with some refinements and a general quality of execution that rise it above its peers. Its overcoiled hairspring and beautifully laid out escapement make it an accurate timekeeper across positions and amplitudes and its interestingly designed center seconds layout give it a thin profile and a smooth second hand with little effort on the part of the adjuster. It represents a level of horological accomplishment in mass-production that was significant and worthy of praise in its day and is now unseen in all but the highest quality timepieces. It is also a beautiful little chunk of history, Schaffhausen style.

All Rights Reserved