Watches Under Water

An abbreviated history of the evolution of the

water resistant wristwatch

By Michael

Friedberg

As

the wristwatch evolved in the 20th century from the pocketwatch, its

public acceptance in large part may be attributed to improvements in its

durability. The early enemies of the wristwatch included water, dust, shocks and

magnetism. It was primarily during the 1920s and ‘30s that engineering advances

occurred in the fight against these forces. The wristwatches that we

know and wear today are products of this evolution.

As

the wristwatch evolved in the 20th century from the pocketwatch, its

public acceptance in large part may be attributed to improvements in its

durability. The early enemies of the wristwatch included water, dust, shocks and

magnetism. It was primarily during the 1920s and ‘30s that engineering advances

occurred in the fight against these forces. The wristwatches that we

know and wear today are products of this evolution.

During the 1930s, shock-proof

mechanisms were developed, including the Incabloc and Kif systems. Also during

this decade various approaches were developed to combat magnetism, including

encapsulating movements in a soft-iron inner case or the use of amagnetic

movement parts, sometimes even including gold. But perhaps the most noteworthy

advance was improving the wristwatch case so that it would sealed.

By doing so, the watch’s internal mechanism would not be affected by either water or dust.

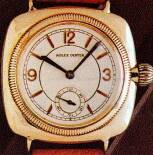

Rolex and Omega, which today are

leaders in the Swiss watch industry, pioneered the fight against water.

While some cases were "well sealed" even before 1920, it was Hans

Wilsdorf of Rolex who perceived an opportunity and, with astute marketing, made Rolex a world famous brand.

In the early 1920s, a famous Swiss casemaker,

Francis Baumgartner, made cases based on a patent by Borgel.

The idea involved sealing

the case by taking the middle part and threading it on both sides, rotating in

opposite directions. The movement and dial then were fited within a ring that screwed

into the caseframe. Several companies then used Baumgartner-made cases in the

1920s, including Omega and Longines. However, the Borgel-based cases

did not seal well at the stem  opening.

To solve that, two Swiss watchmakers in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Paul Perregaux

and Georges Peret, applied for a Swiss patent in 1925 for a screwed stem system.

opening.

To solve that, two Swiss watchmakers in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Paul Perregaux

and Georges Peret, applied for a Swiss patent in 1925 for a screwed stem system.

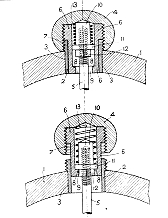

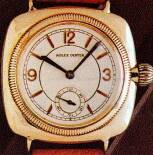

Wilsdorf grasped that a hermetically sealed case, together with careful fitting of the

crystal and a special stem mechanism, would produce a better wristwatch.

He quickly negotiated to have the Perregaux and Peret patent assigned to him.

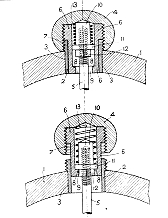

Wilsdorf then obtained a British patent on

October 18, 1926. Drawings from the patent are shown on the

left side.

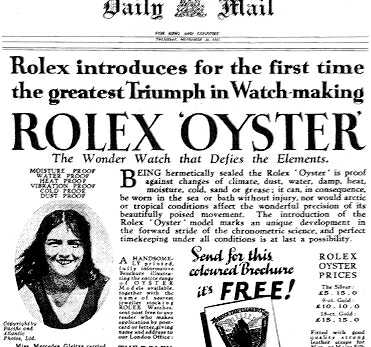

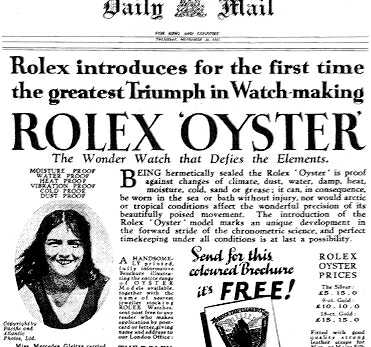

The Rolex Oyster became a

commercial success.. In 1927, a

stenographer, Mercedes Gleitze, swam the English Channel with the unheard of

accompaniment of a wristwatch –the Rolex Oyster— on her wrist for

the entire 15 hour, 15 minute, swim.

The ensuing publicity catapulted

Rolex to a prominent place in the world of watches. The battle against dust and

water had been won. Wilsdorf proclaimed "With this invention, originally

made to increase the precision of the Rolex watch, at the same time the first

waterproof wristwatch of the world was created. Like an oyster, it could remain

in the water a indeterminate time before being damaged."

In 1932, Cartier made a

waterproof wristwatch, using a specially screwed crown. The Pasha of Marrakesh

said to Louis Cartier " I would like to know the exact time while swimming

in my swimming pool." The Pasha achieved his wish and Cartier may have

created the first luxury sports watch in the process.

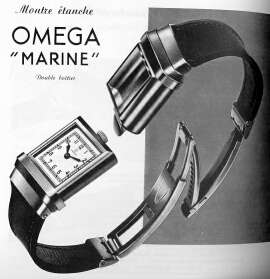

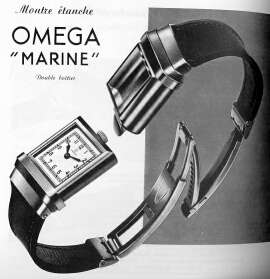

Omega

took a radically different approach. In 1932, it debuted the Omega Marine, a watch that

basically had one case inside another. In 1936, an underwater researcher, Charles William

Beebe, dove to the depth of 14 meters with an Omega Marine strapped to his

diving suit. Before the age of scuba gear, Beebe succeeded wearing a huge

helmet, weighted boots and tubes leading up to the surface, as well as his Omega

Marine.

Omega

took a radically different approach. In 1932, it debuted the Omega Marine, a watch that

basically had one case inside another. In 1936, an underwater researcher, Charles William

Beebe, dove to the depth of 14 meters with an Omega Marine strapped to his

diving suit. Before the age of scuba gear, Beebe succeeded wearing a huge

helmet, weighted boots and tubes leading up to the surface, as well as his Omega

Marine.

Other companies in the late

1930s tried simpler approaches. A well-sealed case, including the use of

gaskets, would be sufficient to provide some reasonable water resistance for

everyday use. The "over-engineering" of greater water resistance made

little difference in normal use – at 5 meters submersion, a watch rated to 10

meters should work equally as well as one rated to 50 meters, all other factors

–including deterioration in seals—being equal.

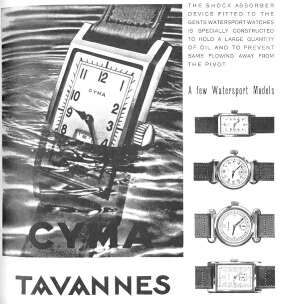

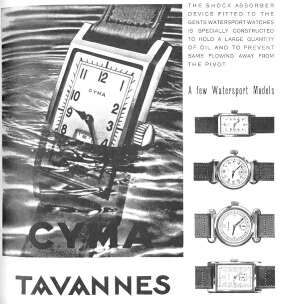

Pictured

here is an advertisement for Cyma watches by Tavannes from the late 1930s,

clearly promoting their water resistant qualities. The style of these cases is

typical of the era and not what we consider today as "dive

watches". Also

depicted, below right, is a page from a 1930s watchmaker's manual, showing the

"waterproof" construction of a Wyler case.

Pictured

here is an advertisement for Cyma watches by Tavannes from the late 1930s,

clearly promoting their water resistant qualities. The style of these cases is

typical of the era and not what we consider today as "dive

watches". Also

depicted, below right, is a page from a 1930s watchmaker's manual, showing the

"waterproof" construction of a Wyler case. It is probable that these Tavannes and Wyler cases were actually made by

Baumgartner, who incidentally also made the original case for the

original Patek Philipe Calatrava "96" model.

It is probable that these Tavannes and Wyler cases were actually made by

Baumgartner, who incidentally also made the original case for the

original Patek Philipe Calatrava "96" model.

In contrast to these

"regular" watches utilizing well made cases, especially water resistant

watches were considered as "tool watches" – designed for a

special purpose and meant to be used in a particular way. Although Rolex

certainly perceived a broad market for its Oyster models, it often concentrated on the military

market, where a particularly "strong" watch would have utility.

Military operations required precise timing, which in turn required a

dependable watch. Such watches needed to consistently withstand water

and dust.

During

World War II, the world’s militaries in practice distinguished between special

diving watches and those having some water resistance. Divers needed heavily

sealed cases and the idea of watches like the Omega Marine did not succeed. Instead, the idea

was to have a large watch with a system to seal the crown and stem --the

parts of a watch that were especially vulnerable to water. Pictured

left is a World War II U.S. Navy "Sea Bees" diving watch made by

Hamilton, with a special double crown mechanism to

make the watch impermeable to water. These models allowed frogmen to descend to

a depth of 50 meters and monitor the time remaining on their air supply. Similar models produced in Russia are

frequently found.

During

World War II, the world’s militaries in practice distinguished between special

diving watches and those having some water resistance. Divers needed heavily

sealed cases and the idea of watches like the Omega Marine did not succeed. Instead, the idea

was to have a large watch with a system to seal the crown and stem --the

parts of a watch that were especially vulnerable to water. Pictured

left is a World War II U.S. Navy "Sea Bees" diving watch made by

Hamilton, with a special double crown mechanism to

make the watch impermeable to water. These models allowed frogmen to descend to

a depth of 50 meters and monitor the time remaining on their air supply. Similar models produced in Russia are

frequently found.

World

War II Italian and German Navy divers adopted a different approach, using a

well sealed watch that later had a special guard to keep the crown (and stem)

flush against the case. Depicted right is an assortment of Panerai dive watches,

together with an underwater depth gauge and compass. The watch at

left used a Rolex movement while the one at right used an Angelus eight-day

movement and has a special crown guard. Originally, the Panerai watches had

unprotected crowns that used the Rolex screw-down mechanism. However, constant

winding of these watches caused deterioration of water resistance. Officine

Panerai solved the problem by a pressure-lever on the crown; those watches

worked at a depth of 30 meters. While historically

interesting, these watches had little utility

for the general military, let alone civilian use, due to their size.

World

War II Italian and German Navy divers adopted a different approach, using a

well sealed watch that later had a special guard to keep the crown (and stem)

flush against the case. Depicted right is an assortment of Panerai dive watches,

together with an underwater depth gauge and compass. The watch at

left used a Rolex movement while the one at right used an Angelus eight-day

movement and has a special crown guard. Originally, the Panerai watches had

unprotected crowns that used the Rolex screw-down mechanism. However, constant

winding of these watches caused deterioration of water resistance. Officine

Panerai solved the problem by a pressure-lever on the crown; those watches

worked at a depth of 30 meters. While historically

interesting, these watches had little utility

for the general military, let alone civilian use, due to their size.

Instead, most World War II

forces –armies, navies and air forces—used watches that simply had

well-sealed cases. The famous "WWW" --wristwatch, waterproof-- of the

British  forces really just used high quality cases that

were well sealed. Many of

these even had snap-on backs, rather than tighter screwed backs, like the IWC

Mark X "WWW" depicted at left. There wasn’t a

perceived need for great water resistance. Even the legendary Mark XI, which

debuted shortly after the war with a screwed back, had British military specifications

requiring it to be water resistant to 10 meters.

forces really just used high quality cases that

were well sealed. Many of

these even had snap-on backs, rather than tighter screwed backs, like the IWC

Mark X "WWW" depicted at left. There wasn’t a

perceived need for great water resistance. Even the legendary Mark XI, which

debuted shortly after the war with a screwed back, had British military specifications

requiring it to be water resistant to 10 meters.

The ultimate evolution of more

water resistant wristwatches may have resulted from clever marketing and a

change in civilian lifestyles. In 1954, Rolex debuted its Ref. 6204 Submariner

model at the Basel

Fair: a dive watch for civilian use. The design was based on Rolex's Ref. 6202

Turn-O-Graph model and over the following decade evolved to look like the watch

we know today. The

Submariner became an instant success and an instant

classic.

marketing and a

change in civilian lifestyles. In 1954, Rolex debuted its Ref. 6204 Submariner

model at the Basel

Fair: a dive watch for civilian use. The design was based on Rolex's Ref. 6202

Turn-O-Graph model and over the following decade evolved to look like the watch

we know today. The

Submariner became an instant success and an instant

classic.

The original Submariner, Ref.

6204, did not have Mercedes hands and had many other small differences from the

current model. Two years later, in 1956, it was replaced with the Ref. 6538

--the "James Bond" Submariner (above right), which was the first watch

rated to a depth of 660 feet. It looked much more like the current model

except that it did not have crown guards. Various other evolutionary changes

occurred in the Submariner's design over the ensuing decades. This time, the military market adopted the civilian model, as

the illustration at right of a Ref. 5513 Submariner from the late 1960s

depicts. That model was issued to Royal Navy frogmen and had fixed lugs, as well

as T in a circle on the dial which denoted tritium.

There is some debate regarding

whether Rolex produced the first civilian "dive watch" with its

Submariner model. Certainly, it debuted a long time after the Omega Marine,

but that model was not a great success and perhaps with hindsight can be

regarded as a historical anomaly. But in the early 1950s the Submariner had a

profound effect on the market. While not unique, the idea of a bezel that could

be turned unidirectionally to tell elapsed time became identified with the

"dive watch".

There are claims that Blancpain,

with its 50 Fathoms model, preceded the Submariner by a few months and was first

used in a film made in late 1953. Blancpain

successfully marketed its watch with Jacques Cousteau, the famous undersea diver, and later came out with

its Aqualung and Bathyscaphe models as well. Blancpain

also sold its 50 Fathoms watches for military use, as the German Navy model at

right reflects.

There are claims that Blancpain,

with its 50 Fathoms model, preceded the Submariner by a few months and was first

used in a film made in late 1953. Blancpain

successfully marketed its watch with Jacques Cousteau, the famous undersea diver, and later came out with

its Aqualung and Bathyscaphe models as well. Blancpain

also sold its 50 Fathoms watches for military use, as the German Navy model at

right reflects.

The success of these models can

be attributed to being right for their times. Professor Picard in September 1953 descended to a depth of 3,150 meters in a

bathyscaphe with a watch made by

Rolex strapped to the outside of the capsule. Scuba diving was developed

and rocketed in popularity in the 1950s. The explorations of Cousteau and even

Lloyd Bridges in television's "Sea Hunt" program

reinforced the public interest in diving.

Following in the wake of Rolex

and Blancpain’s introductions, many other companies then produced, and perhaps

more importantly successfully marketed, diving watches. Virtually all of the famous Swiss

marques, except perhaps Patek Phillipe and Audemars Piguet, followed in the

1950s and 1960s. At the 1955 Basel Fair, Eterna launched its Kon-Tiki model.

Subsequently, Longines produced a diving watch and Girard Perregaux also produced one with a 36,000 bph fast beat

movement. International Watch Company introduced its first diving watch

around 1964 with

its Aquatimer (depicted right). Jaeger LeCoultre produced a special

diving watch with alarm, the Polaris, as did Vulcain with its Cricket-Nautical

model that also had a pressure indicator. In 1971, Rolex introduced its Sea

Dweller model that had a gas escape valve to equalize pressure from helium.

produced one with a 36,000 bph fast beat

movement. International Watch Company introduced its first diving watch

around 1964 with

its Aquatimer (depicted right). Jaeger LeCoultre produced a special

diving watch with alarm, the Polaris, as did Vulcain with its Cricket-Nautical

model that also had a pressure indicator. In 1971, Rolex introduced its Sea

Dweller model that had a gas escape valve to equalize pressure from helium.

Omega embraced the burgeoning market with enthusiasm. Although it

originally produced a Seamaster model in 1948, that model was not a diving

watch. Omega debuted its first dive model Seamaster, the 300 (which had a

water resistance to 200 meters), in 1957 and which used Omega's 20 jewel

Cal. 28 SC-501 movement.

Omega embraced the burgeoning market with enthusiasm. Although it

originally produced a Seamaster model in 1948, that model was not a diving

watch. Omega debuted its first dive model Seamaster, the 300 (which had a

water resistance to 200 meters), in 1957 and which used Omega's 20 jewel

Cal. 28 SC-501 movement.  It redesigned the Seamaster 300 in 1965

(depicted right) and,

following that model's success, then introduced many new models -- the Seamaster

120 in 1966, the Seamaster 600 in 1970 and the Seamaster 1000 (with a

corresponding 1000 meter water resistance) in 1971. At one time, Omega even introduced

a rectangular Marine Chronometer with a 300 Hz electronic

movement --a model

It redesigned the Seamaster 300 in 1965

(depicted right) and,

following that model's success, then introduced many new models -- the Seamaster

120 in 1966, the Seamaster 600 in 1970 and the Seamaster 1000 (with a

corresponding 1000 meter water resistance) in 1971. At one time, Omega even introduced

a rectangular Marine Chronometer with a 300 Hz electronic

movement --a model  that stylistically was inspired by its original Marine model.

The evolution of Omega's models continued throughout the 1970s and '80s, reflecting both

Omega's emphasis on the market and the public demand for sports watches with

high degrees of water resistance.

that stylistically was inspired by its original Marine model.

The evolution of Omega's models continued throughout the 1970s and '80s, reflecting both

Omega's emphasis on the market and the public demand for sports watches with

high degrees of water resistance.

Even the luxury companies

eventually followed suit, at least in their own way. In 1972,

Audemars Piguet introduced its Royal Oak model, a luxury sports watch with a nautical theme and

porthole design, shown at right. Patek Philipe soon followed with its Nautilus: again a watch with a nautically-related

theme, but

certainly not a

true dive watch. Far from being tool watches, the Royal Oak and Nautilus

models reflected that watches were marketed for what they evoked, both through

their names and their designs.

Royal Oak model, a luxury sports watch with a nautical theme and

porthole design, shown at right. Patek Philipe soon followed with its Nautilus: again a watch with a nautically-related

theme, but

certainly not a

true dive watch. Far from being tool watches, the Royal Oak and Nautilus

models reflected that watches were marketed for what they evoked, both through

their names and their designs.

Today, water resistance is both

taken for granted and perhaps exaggerated in importance. Extraordinary water

resistance often is a badge of

durability, but in a sense over-engineering arguably may be used as a marketing

vehicle. Beginning in the 1970s, some wristwatches had

water resistance ratings of 1000 or 2000 meters, yet it is impractical for any human to

descend  to anything close to such depths. Even the famous IWC

Porsche Design Ocean 2000 –with a huge water

resistance of 2000 meters—was scaled back to "only" 300 meters in its "3H"

version made for German Navy divers. IWC’s Deep One model, the first

mechanical watch was a mechanical depth gauge and a model made expressly for

diving, only has a water resistance of 100 meters. IWC claims that

such a depth is the maximum safe one for amateur divers.

to anything close to such depths. Even the famous IWC

Porsche Design Ocean 2000 –with a huge water

resistance of 2000 meters—was scaled back to "only" 300 meters in its "3H"

version made for German Navy divers. IWC’s Deep One model, the first

mechanical watch was a mechanical depth gauge and a model made expressly for

diving, only has a water resistance of 100 meters. IWC claims that

such a depth is the maximum safe one for amateur divers.

Dive watches continue to enjoy

immense popularity. They are practical, sporty and fun watches. Matching

contemporary lifestyles, their popularity is well deserved. Even out of the

water, they subtly --perhaps subconsciously-- reinforce the idea of a casual

lifestyle. And more than being reflective of the times, these watches also reflect a historical

tradition.

swim

Copyright

2000

Michael

Friedberg

PastTime

All

rights reserved

Special

thanks to Z. Wesolowski who provided the images of the Hamilton, Panerai and Rolex

Military Submariner

watches from his book A Concise Guide to Military Timepieces, 1880-1990.

The image of the Bond Submariner is courtesy of Clemens von Halem; the vintage

IWC Aquatimer and Porsche Design Ocean 2000 models are courtesy of R. Kammer.

Back to top of page | Return to Time Zone Home Page

Copyright © 1998-2000 Ashford Buying Co. Inc., All Rights Reserved

E-mail: info@TimeZone.com

As

the wristwatch evolved in the 20th century from the pocketwatch, its

public acceptance in large part may be attributed to improvements in its

durability. The early enemies of the wristwatch included water, dust, shocks and

magnetism. It was primarily during the 1920s and ‘30s that engineering advances

occurred in the fight against these forces. The wristwatches that we

know and wear today are products of this evolution.

As

the wristwatch evolved in the 20th century from the pocketwatch, its

public acceptance in large part may be attributed to improvements in its

durability. The early enemies of the wristwatch included water, dust, shocks and

magnetism. It was primarily during the 1920s and ‘30s that engineering advances

occurred in the fight against these forces. The wristwatches that we

know and wear today are products of this evolution. opening.

To solve that, two Swiss watchmakers in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Paul Perregaux

and Georges Peret, applied for a Swiss patent in 1925 for a screwed stem system.

opening.

To solve that, two Swiss watchmakers in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Paul Perregaux

and Georges Peret, applied for a Swiss patent in 1925 for a screwed stem system.

Omega

took a radically different approach. In 1932, it debuted the Omega Marine, a watch that

basically had one case inside another. In 1936, an underwater researcher, Charles William

Beebe, dove to the depth of 14 meters with an Omega Marine strapped to his

diving suit. Before the age of scuba gear, Beebe succeeded wearing a huge

helmet, weighted boots and tubes leading up to the surface, as well as his Omega

Marine.

Omega

took a radically different approach. In 1932, it debuted the Omega Marine, a watch that

basically had one case inside another. In 1936, an underwater researcher, Charles William

Beebe, dove to the depth of 14 meters with an Omega Marine strapped to his

diving suit. Before the age of scuba gear, Beebe succeeded wearing a huge

helmet, weighted boots and tubes leading up to the surface, as well as his Omega

Marine. Pictured

here is an advertisement for Cyma watches by Tavannes from the late 1930s,

clearly promoting their water resistant qualities. The style of these cases is

typical of the era and not what we consider today as "dive

watches". Also

depicted, below right, is a page from a 1930s watchmaker's manual, showing the

"waterproof" construction of a Wyler case.

Pictured

here is an advertisement for Cyma watches by Tavannes from the late 1930s,

clearly promoting their water resistant qualities. The style of these cases is

typical of the era and not what we consider today as "dive

watches". Also

depicted, below right, is a page from a 1930s watchmaker's manual, showing the

"waterproof" construction of a Wyler case. It is probable that these Tavannes and Wyler cases were actually made by

Baumgartner, who incidentally also made the original case for the

original Patek Philipe Calatrava "96" model.

It is probable that these Tavannes and Wyler cases were actually made by

Baumgartner, who incidentally also made the original case for the

original Patek Philipe Calatrava "96" model. During

World War II, the world’s militaries in practice distinguished between special

diving watches and those having some water resistance. Divers needed heavily

sealed cases and the idea of watches like the Omega Marine did not succeed. Instead, the idea

was to have a large watch with a system to seal the crown and stem --the

parts of a watch that were especially vulnerable to water. Pictured

left is a World War II U.S. Navy "Sea Bees" diving watch made by

Hamilton, with a special double crown mechanism to

make the watch impermeable to water. These models allowed frogmen to descend to

a depth of 50 meters and monitor the time remaining on their air supply. Similar models produced in Russia are

frequently found.

During

World War II, the world’s militaries in practice distinguished between special

diving watches and those having some water resistance. Divers needed heavily

sealed cases and the idea of watches like the Omega Marine did not succeed. Instead, the idea

was to have a large watch with a system to seal the crown and stem --the

parts of a watch that were especially vulnerable to water. Pictured

left is a World War II U.S. Navy "Sea Bees" diving watch made by

Hamilton, with a special double crown mechanism to

make the watch impermeable to water. These models allowed frogmen to descend to

a depth of 50 meters and monitor the time remaining on their air supply. Similar models produced in Russia are

frequently found. World

War II Italian and German Navy divers adopted a different approach, using a

well sealed watch that later had a special guard to keep the crown (and stem)

flush against the case. Depicted right is an assortment of Panerai dive watches,

together with an underwater depth gauge and compass. The watch at

left used a Rolex movement while the one at right used an Angelus eight-day

movement and has a special crown guard. Originally, the Panerai watches had

unprotected crowns that used the Rolex screw-down mechanism. However, constant

winding of these watches caused deterioration of water resistance. Officine

Panerai solved the problem by a pressure-lever on the crown; those watches

worked at a depth of 30 meters. While historically

interesting, these watches had little utility

for the general military, let alone civilian use, due to their size.

World

War II Italian and German Navy divers adopted a different approach, using a

well sealed watch that later had a special guard to keep the crown (and stem)

flush against the case. Depicted right is an assortment of Panerai dive watches,

together with an underwater depth gauge and compass. The watch at

left used a Rolex movement while the one at right used an Angelus eight-day

movement and has a special crown guard. Originally, the Panerai watches had

unprotected crowns that used the Rolex screw-down mechanism. However, constant

winding of these watches caused deterioration of water resistance. Officine

Panerai solved the problem by a pressure-lever on the crown; those watches

worked at a depth of 30 meters. While historically

interesting, these watches had little utility

for the general military, let alone civilian use, due to their size. forces really just used high quality cases that

were well sealed. Many of

these even had snap-on backs, rather than tighter screwed backs, like the IWC

Mark X "WWW" depicted at left. There wasn’t a

perceived need for great water resistance. Even the legendary Mark XI, which

debuted shortly after the war with a screwed back, had British military specifications

requiring it to be water resistant to 10 meters.

forces really just used high quality cases that

were well sealed. Many of

these even had snap-on backs, rather than tighter screwed backs, like the IWC

Mark X "WWW" depicted at left. There wasn’t a

perceived need for great water resistance. Even the legendary Mark XI, which

debuted shortly after the war with a screwed back, had British military specifications

requiring it to be water resistant to 10 meters. marketing and a

change in civilian lifestyles. In 1954, Rolex debuted its Ref. 6204 Submariner

model at the Basel

Fair: a dive watch for civilian use. The design was based on Rolex's Ref. 6202

Turn-O-Graph model and over the following decade evolved to look like the watch

we know today. The

Submariner became an instant success and an instant

classic.

marketing and a

change in civilian lifestyles. In 1954, Rolex debuted its Ref. 6204 Submariner

model at the Basel

Fair: a dive watch for civilian use. The design was based on Rolex's Ref. 6202

Turn-O-Graph model and over the following decade evolved to look like the watch

we know today. The

Submariner became an instant success and an instant

classic.  There are claims that Blancpain,

with its 50 Fathoms model, preceded the Submariner by a few months and was first

used in a film made in late 1953. Blancpain

successfully marketed its watch with Jacques Cousteau, the famous undersea diver, and later came out with

its Aqualung and Bathyscaphe models as well. Blancpain

also sold its 50 Fathoms watches for military use, as the German Navy model at

right reflects.

There are claims that Blancpain,

with its 50 Fathoms model, preceded the Submariner by a few months and was first

used in a film made in late 1953. Blancpain

successfully marketed its watch with Jacques Cousteau, the famous undersea diver, and later came out with

its Aqualung and Bathyscaphe models as well. Blancpain

also sold its 50 Fathoms watches for military use, as the German Navy model at

right reflects.  produced one with a 36,000 bph fast beat

movement. International Watch Company introduced its first diving watch

around 1964 with

its Aquatimer (depicted right). Jaeger LeCoultre produced a special

diving watch with alarm, the Polaris, as did Vulcain with its Cricket-Nautical

model that also had a pressure indicator. In 1971, Rolex introduced its Sea

Dweller model that had a gas escape valve to equalize pressure from helium.

produced one with a 36,000 bph fast beat

movement. International Watch Company introduced its first diving watch

around 1964 with

its Aquatimer (depicted right). Jaeger LeCoultre produced a special

diving watch with alarm, the Polaris, as did Vulcain with its Cricket-Nautical

model that also had a pressure indicator. In 1971, Rolex introduced its Sea

Dweller model that had a gas escape valve to equalize pressure from helium. Omega embraced the burgeoning market with enthusiasm. Although it

originally produced a Seamaster model in 1948, that model was not a diving

watch. Omega debuted its first dive model Seamaster, the 300 (which had a

water resistance to 200 meters), in 1957 and which used Omega's 20 jewel

Cal. 28 SC-501 movement.

Omega embraced the burgeoning market with enthusiasm. Although it

originally produced a Seamaster model in 1948, that model was not a diving

watch. Omega debuted its first dive model Seamaster, the 300 (which had a

water resistance to 200 meters), in 1957 and which used Omega's 20 jewel

Cal. 28 SC-501 movement.  It redesigned the Seamaster 300 in 1965

(depicted right) and,

following that model's success, then introduced many new models -- the Seamaster

120 in 1966, the Seamaster 600 in 1970 and the Seamaster 1000 (with a

corresponding 1000 meter water resistance) in 1971. At one time, Omega even introduced

a rectangular Marine Chronometer with a 300 Hz electronic

movement --a model

It redesigned the Seamaster 300 in 1965

(depicted right) and,

following that model's success, then introduced many new models -- the Seamaster

120 in 1966, the Seamaster 600 in 1970 and the Seamaster 1000 (with a

corresponding 1000 meter water resistance) in 1971. At one time, Omega even introduced

a rectangular Marine Chronometer with a 300 Hz electronic

movement --a model  that stylistically was inspired by its original Marine model.

The evolution of Omega's models continued throughout the 1970s and '80s, reflecting both

Omega's emphasis on the market and the public demand for sports watches with

high degrees of water resistance.

that stylistically was inspired by its original Marine model.

The evolution of Omega's models continued throughout the 1970s and '80s, reflecting both

Omega's emphasis on the market and the public demand for sports watches with

high degrees of water resistance. Royal Oak model, a luxury sports watch with a nautical theme and

porthole design, shown at right. Patek Philipe soon followed with its Nautilus: again a watch with a nautically-related

theme, but

certainly not a

true dive watch. Far from being tool watches, the Royal Oak and Nautilus

models reflected that watches were marketed for what they evoked, both through

their names and their designs.

Royal Oak model, a luxury sports watch with a nautical theme and

porthole design, shown at right. Patek Philipe soon followed with its Nautilus: again a watch with a nautically-related

theme, but

certainly not a

true dive watch. Far from being tool watches, the Royal Oak and Nautilus

models reflected that watches were marketed for what they evoked, both through

their names and their designs. to anything close to such depths. Even the famous IWC

Porsche Design Ocean 2000 –with a huge water

resistance of 2000 meters—was scaled back to "only" 300 meters in its "3H"

version made for German Navy divers. IWC’s Deep One model, the first

mechanical watch was a mechanical depth gauge and a model made expressly for

diving, only has a water resistance of 100 meters. IWC claims that

such a depth is the maximum safe one for amateur divers.

to anything close to such depths. Even the famous IWC

Porsche Design Ocean 2000 –with a huge water

resistance of 2000 meters—was scaled back to "only" 300 meters in its "3H"

version made for German Navy divers. IWC’s Deep One model, the first

mechanical watch was a mechanical depth gauge and a model made expressly for

diving, only has a water resistance of 100 meters. IWC claims that

such a depth is the maximum safe one for amateur divers.