Biver and Piguet: The Lost Works. June 15, 2000

"We wanted only the round shape, and the simplicity of just one model of watchcase to give to the essence of the watch, the movement, the first role...One case, but a complete choice of classical mechanical movements, all providing one or more extra functions in an extra-thin configuration...No concept could be purer than this one!"

-- Jean-Claude Biver to Michael Friedberg

It was at the lowest point in the history of Swiss watchmaking, where the old great names were merely brands stamped upon quartz timekeepers and other hideous artifacts best left unmentioned, that Jacques Piguet (of Frederic Piguet) and Jean-Claude Biver (of Omega) set out to preserve and advance the traditional art of mechanical watchmaking with a narrowly focused line of six watches -- all in extra-thin 33mm cases, and each of which may be considered one of the great challenges of fine watchmaking. In Blancpain's present marketing parlance they are the "Six Masterpieces."

"Blancpain" is a name well known to the afficianados of modern fine watchmaking -- a name not without controversy due to marketing which alludes to a history reaching back over 260 years, but whose watches are based on a very real heritage of continuous design, development, and manufacture of ebauches and complications for nearly 150 years (since 1858) -- at Frederic Piguet. It is this foundation of real watchmaking that permitted Blancpain from the outset to produce what may be the finest single line of watch models in any brand's portfolio. While I have been assured that these watches of classical proportion and design continue to sell well in the marketplace, they have fallen into relative obscurity within the conciousness of the enthusiast community, a result of factors in both the industry and the market.

While a small private company can pursue unique ideals like the one that the modern Blancpain was founded on, including an intentionally limited production, the coporate reality of the reacquisition of the Blancpain brand by SMH (now the Swatch Group) is that "growth" of the brand became a necessity. This meant new models, increased production, and of course new and broader marketing.

The present market trend to larger, often oversized "sports" watches has been met with the addition of the very popular 2100 and Trilogy models. The 2100, the first line introduced by Blancpain under SMH, combines a large 38mm case with the 100m water resistance rating made popular by Rolex -- the standard minimum for "rugged" watches. The more recently introduced Trilogy series attempts to outdo the Rolex Professional line and similar watches, by being the most luxurious instrument-style watches in production. Sadly, with the "Concept 2000" Trilogy variants, Blancpain does Bvlgari.

This seemingly endless stream of new models provides much grist for the mill of watch discussion and consumption, yet I expect that there are a few of us left that prefer the refined over the needlessly large and rugged. It is for us to turn back to the original vision of authentic haute horlogerie encompassed by a small family of six watches.

The quantieme a phase de la lune is a classic complication that is not only more accessible than perpetual calendars, but I find that its particular character and symmetry is often more elegant as well. It is appropriate that it is this complication that marked the inception of the modern (but pre-SMH) Blancpain and its purist philosophy.

This first model from Blancpain also introduces us to the many advantages of Frederic Piguet's extensive use of modular construction. For the early edition of this watch the impeccably crafted "complete calendar" module 65 was based on F. Piguet's 953, a small 9''' automatic with unidirectional winding (calibre 6595). The introduction of the much more advanced 11''' automatic in 1988 prompted a redesign using module 65 placed upon the 1153 (calibre 6553). The manually wound version of this watch also uses the 65, but mounted I believe upon the ETA-Peseux 7001 (calibre 6501).

A quantieme perpetual was Blancpain's other initial public offering, and if there is any watch that is the darling of complication connoisseurs, it is the perpetual calendar. The original model has a clean, uncluttered clarity common to many classic perpetuals that dispense with year indication (leap or numeric). It remains the only pure perpetual calendar watch in the Blancpain portfolio.

This watch has evolved along similar lines to the complete calendar model. The original module 53 was also based on Piguet's 953 automatic (calibre 5395), but in this case the adoption of the 1153 as a base movement to replace the 953 also brought the introduction of a more complex perpetual calendar plate with leap year pointer: Module 54 (calibre 5453). This resulted in a watch that is both more complex and advanced technically, but at the steep cost of a retail price nearly 50% higher.

Ultrathins have long been a hallmark of fine watchmaking and good taste. Made possible only by highly refined craftsmanship, the ultrathin mechanical exists as a product exclusive to a handful of manufacturers, as the delicate and tempermental movements within can only be handled by an expert watchmaker. On a personal side note, it was when I was seeking information on Blancpain's "Ultraslim" that I first discovered Timezone (in 1998).

The 9''' calibre 21 used in the Ultraslim is essentially the venerable calibre 99 advanced from 18,000bph to 21,600bph. The 99/21 could be considered the archetype of ultrathin handwinds, with a history going back to dawn of the wristwatch era (in development from 1911 to 1925). It is also used by Patek Philippe for its ultrathins as calibre 177.

The most expensive single complication in the Masterpiece collection, the minute repeater manages to appear to be nothing more than a rather understated, simple thin watch. The slide that activates the repetition function limits the case to being merely "water resistant," whereas the other five watches of the Masterpiece collection are pressure tested to 30m. I think that the beauty of repeaters lies less in the ringing of hand-tuned notes, than in the elegant design of the calibres and in the craftsmanship lavished upon their construction.

Calibre 33 is a completely traditional hand-wound minute repeater design, very much akin to Lemania's calibre 399 and the classical repeater designs of Christophe Claret and Renaud et Papi (of Audemars Piguet), which is somewhat odd for Frederic Piguet given their well deserved reputation for innovation. Featuring a screwed balance wheel, overcoil hairspring, and gilding rather than rhodium plating, it hardly seems to be an F. Piguet calibre at all.

It was once explained to me by a watchmaker from a small manufacture in Fleurier, that chronographs are much favoured by collectors in that they permit the collector to acquire a "complicated" watch for typically a small premium over the price of a simple automatic or handwind. With the rattrapante, the accessible "tool watch" is translated into a rarefied yet functional work of the craftsman's art, and as I am inclined to think of the chronograph as a basic form of watch, it is the addition of the splits-second function that more appropriately qualifies the rattrapante for consideration as a complication. A classical rattrapante with two column wheels co-ordinating the various operations, like Blancpain's 1181, is no doubt worthy of inclusion onto a narrow list of six great challenges of fine watchmaking.

The rattrapante calibre 1181 and its automatic variant 1186, are the final flower of Piguet chronograph design, and the result of a very large gamble taken by the fledgling Blancpain brand in the creation of a completely new and innovative chronograph calibre. In-depth information on this calibre can be found in the Horologium, or by clicking here.

My only objection in the design of Blancpain's Rattrapante is the inclusion of the date guichet which in my opinion is as out of place here as it would be on the Ultraslim. At least it has been integrated in the least obtrusive way possible.

I find it strange that Blancpain's 1181 and 1186 are the only pure rattrapante watches at this level of manufacture in regular production. The rattrapantes of manufactures like Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet are limited to being parts of more complicated watches -- the 5004 and Grande Complication respectively. This distinction adds yet another feather to Blancpain's cap.

Finally we have a somewhat controversial complication, the tourbillon watch. The questionable status of tourbillon watches as complications lies in their very lack of complexity, and to the question of whether they perform as claimed. Yet the combination of the high manufacturing cost due to factors like the great difficulty in adjustment and regulation, as well as the almost magical animation of the escapement, combine to make an expensive, rare, and thus desireable "complication" even it does little for the real world accuracy of a wristwatch.

This tourbillon's calibre is a technical and aesthetic marvel: The "flying" type of tourbillon which is usually only found in limited editions is a feature of the regular production calibre 23, with the unique refinement of an eccentric, free-sprung, screwed balance wheel. Isochronism is optimized by the ample eight-day power reserve, which is achieved with just a single mainspring barrel. According to Timezone's resident technical maven Walt Odets, the use of two crown wheels in this calibre permits gearing that allows the very long power reserve to be fully wound with no more turns of the crown than for ordinary handwinds with a two-day power reserve -- another blessing of the calibre's radical design which dispenses with the 3/4 top-plate construction so common to traditional tourbillons in favour of uniquely sculpted bridges. Even if the tourbillon adds nothing to the function of this simple 19-jewel handwind, the movement is still a wonderfully executed and very modern interpretation of an old challenge in watchmaking.

While Blancpain has become a somewhat different company in its new place within the Swatch Group, the original vision of Biver and Piguet lives yet in these rare and little-seen models -- the only such complete line of its kind by any brand. They may lack the marketing appeal of trendier, larger watches, but they have a timeless classicism that allows them to be appropriate in any age, century, or millennium.

***

Many thanks to Mike Margolis for his generous assistance.

Photo credits:

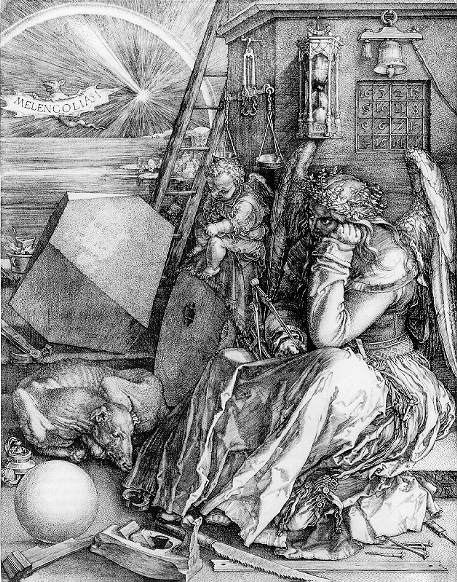

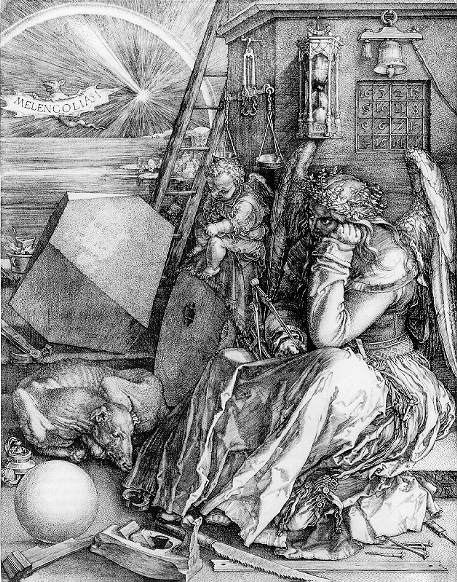

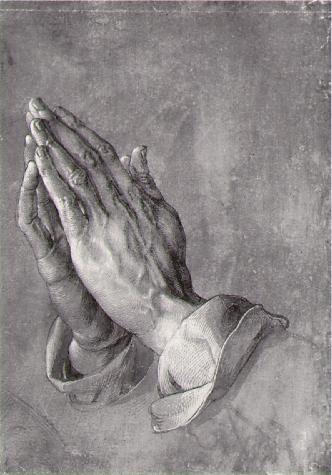

Melancholia I (1516), and Study of Praying Hands (1508), by Albrecht Durer (1471 - 1528); scans by Mark Harden.

Ultraslim and calibre 21 by Mike Margolis.

0023 by Blancpain, S.A.

Calibre 23 by Blancpain, S.A.; scan by Walt Odets.

Used with permission.

Back to top of page | Return to Time Zone Home Page

Copyright © 2001-2004 A Bid Of Time, Inc., All Rights Reserved

E-mail: info@TimeZone.com